|

OBJECTING TO WAR

FIRST CO TO DIE

2 EUROPE GOES TO WAR

3 COUNTDOWN TO CONSCRIPTION

4 FUNDAMENTAL CHANGE IN SOCIETY

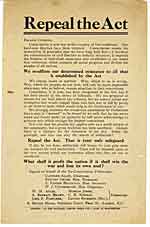

5 NO CONSCRIPTION FELLOWSHIP

6 THE SECRET PRESS

7 MANY TRADITIONS

8 THE TRIBUNALS

9 TRANSCRIPS

10 THE 'won't-fight-funks'

11 THE COST OF CONSCIENCE

12 UNWILLING SOLDIERS

13 ALTERNATIVES AND DILEMMAS

14 PRISON

15 THE MEN SENTENCED TO DEATH

16 COERCION FAILS

17 DYCE

18 DARTMOOR

19 THEY WORK IN OVERCOATS

20 THE MEN WHO DIED

21 WINDING DOWN

21 SELECTION OF BOOKS

22 FROM CALL UP TO DISCHARGE

WHY WAR? supplement

London. Married men protesting at the likelihood of them being conscripted.

|

enlarge

Not much effort was made to find the right sort of people to serve on the Tribunals: people who had some sympathy for socialism or strict religious beliefs. In fact members were almost all elderly local businessmen, ex-civil servants, former policemen, and shop-owners: middle-class and firmly committed to the war. Clergymen also served on many Tribunals, but they too were pro-war. The few women members, to some people’s surprise, were almost always harder on conscientious objectors than the men.

:: tribunal transcript

MARRIED MEN

The 'need' to replace the dead on the battlefield meant that all previous promises made by the Prime Minister and government not to conscript married men had to be reneged on.

The Derby Scheme

|

|

8 THE TRIBUNALS

enlarge

Tribunal sitting. 1916. Note the military representative on the right

People expected that the Tribunals assessing COs would be independent judicial bodies, presided over by fair-minded men and women. As it turned out, they were exactly the same Tribunals which had been set up to facilitate recruitment for the army and continued to fulfil that function.. Most of them found it difficult to change their attitude, even though they were told to give every consideration to men ‘whose objection generally rests on religious or moral conviction’.

The situation was made more difficult because no one had worked out any guidelines. What exactly would qualify a man for conscientious exemption from military service? Did it apply to every man who had a political and moral objection to war? Or only to those with religious convictions (the only category some politicians were ready to accept)?

But many Tribunal members – as well as the statutory Military Representatives – did not really care about these distinctions. Their aim was what it had been: to get men out to the battlefront, not give them the freedom to stay at home. They had little sympathy for the men who appeared before them, and even less understanding of their points of view. As a result the Tribunals caused untold, and utterly pointless, harm to tens of thousands of men and their families.

In the spring of 1916 some 2,000 Tribunals around the country prepared to hear why so many unmarried men did not want to fight. (Only 10% were conscientious objectors.) Some men turned up at their tribunal hearing of their own accord, but many had to be rounded up from their various places of occupation, such as schools, banks, offices and farms. As the numbers being processed grew, the time given to hear them dwindled to a few minutes, and the Tribunals’ tolerance dwindled too. This was particularly tough on the COs: many of them had prepared arguments and expected to be listened to. ‘Do you wash yourself?’ one chairman asked a young religious objector. ‘You don’t look as if you do. Yours is a case of an unhealthy mind in an unwholesome body.’

|