|

OBJECTING TO WAR

FIRST CO TO DIE

2 EUROPE GOES TO WAR

3 COUNTDOWN TO CONSCRIPTION

4 FUNDAMENTAL CHANGE IN SOCIETY

5 NO CONSCRIPTION FELLOWSHIP

6 THE SECRET PRESS

7 MANY TRADITIONS

8 THE TRIBUNALS

9 TRANSCRIPS

10 THE 'won't-fight-funks'

11 THE COST OF CONSCIENCE

12 UNWILLING SOLDIERS

13 ALTERNATIVES AND DILEMMAS

14 PRISON

15 THE MEN SENTENCED TO DEATH

16 COERCION FAILS

17 DYCE

18 DARTMOOR

19 THEY WORK IN OVERCOATS

20 THE MEN WHO DIED

21 WINDING DOWN

21 SELECTION OF BOOKS

22 FROM CALL UP TO DISCHARGE

WHY WAR? supplement

|

Here you can study Jack's journey through the war through official documents - from call up to discharge

Printable versions of these documents for classroom use are available

|

22 FROM CALL UP TO DISCHARGE - Jack Sadler's story through documents

John George Sadler (always known as Jack) was 28 in 1916. He was a self-employed jobbing builder in Byker, Newcastle-on-Tyne. He believed that if there were no armies or navies there would be no war, and the way to stop war would be for everyone to refuse to join the armed forces. When conscription came, he and his two brothers, James and Mark, refused call-up. Jack applied to his local Tribunal in Newcastle for recognition as a conscientious objector, which would exempt him from military service. Find out more about Jack here.

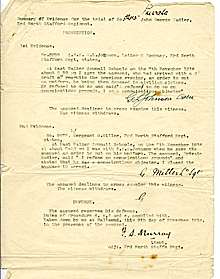

Transcript of Newcastle Local Tribunal hearing, 28 March 1916

Jack was heard unsympathetically, being shouted down by some members of the Tribunal, which refused him any recognition as a conscientious objector.

Report of Tribunal hearings in The Illustrated Chronicle, 29 March 1916

The majority of conscientious objection cases, including that of Jack and his brother James, were refused completely by the Tribunal that day, but two applicants were permitted non-combatant duties in the army.

Notice of Appeal to the Northumberland Appeal Tribunal

Jack appealed to the Northumberland Appeal Tribunal, pointing out that the government had promised to exempt genuine objectors from conscription, and declaring that he would never do what was morally wrong – i.e. join the Army – even if the government ordered him to.

Decision of Northumberland Appeal Tribunal

The Appeal Tribunal, sitting on 11 May 1916, agreed that Jack was a genuine conscientious objector, but decided not to exempt him absolutely from any service. Instead, they ordered him to get a civilian job involving 'work of national importance', and to report back within one month on what job he had started.

Military Service Exemption Certificate

Anyone exempted from Military Service was given a certificate of exemption to be shown to a police officer, employer, or anyone else with a right to question his status under the Military Service Acts. There is a space for Jack to sign the card, but he did not sign it. This was because Jack, as an 'absolutist', claimed the right – allowed by the law – to be exempted absolutely from any service. He felt that to accept 'work of national importance', even civilian work, would be to act as a cog in the machinery of a state geared for total war. He had no problems about playing a useful part in community life – and believed that his own job contributed towards that – but he did not agree that the warfare state had the right to order him what work to do.

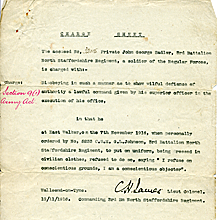

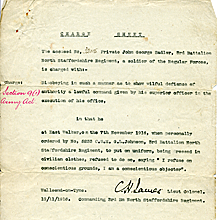

Court-Martial Charge Sheet

Jack carried on with his own job, living his normal life. The month allowed him by the Appeal Tribunal passed by without his reporting back on 'work of national importance'. His exemption therefore lapsed, and his name was passed to the Army for call-up. He was sent a notice to report to barracks for training, but he ignored it. On Friday 3 November 1916 a civilian policeman called at his house and arrested him as an absentee from the Army. He was held overnight in the cells at the police station, and the next morning he was brought before Newcastle Magistrates’ Court, charged with being an absentee. He was fined about £2, and handed over to an Army escort. He was taken to a unit in Newcastle of the 3rd Battalion of the North Staffordshire Regiment, formally enlisted without his consent on Monday 6 November, and on the following day, 7 November, was officially ordered by the Company Sergeant-Major to put on Army uniform. He refused, and was charged with the military offence of disobedience.

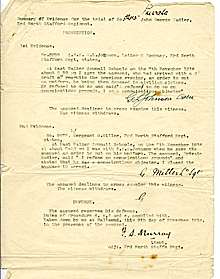

Court-Martial Summary of Evidence

The evidence shows that Jack’s reason for refusal was that he was a conscientious objector, even though the Army regarded him as 'Private Sadler', with his regimental number. In due course, Jack was brought before an Army Court-Martial, where he was convicted of disobedience and sentenced to two years imprisonment with hard labour (meaning that he was deprived of a mattress for the first four weeks), but the sentence was commuted to six months. Military sentences of imprisonment are served in civilian prisons, and Jack served his sentence partly in Newcastle Prison, and partly in Wandsworth and Wormwood Scrubs Prisons, London.

Letter from Central Tribunal

The increasing number of COs in prison led the government to arrange for the Central Tribunal (an overarching tribunal for the whole of Britain) to review all cases of men who had been sentenced to at least three months imprisonment, and, if satisfied that a man was a 'genuine' conscientious objector, to offer him both release from prison and suspension from Army service, on condition of accepting a special scheme of civilian work set up under the Home Office. A letter dated 9 January 1917 offered Jack an interview in Wormwood Scrubs for this purpose, which Jack accepted. The Central Tribunal confirmed the view of the Northumberland Appeal Tribunal that Jack was a genuine objector, but Jack again argued that he was unable to accept the Home Office Scheme, on the same grounds as those on which he had refused the condition of work of national importance.

Letter to Newcastle Local Tribunal

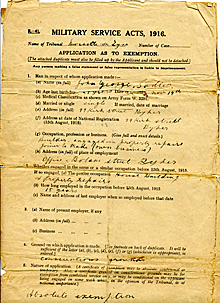

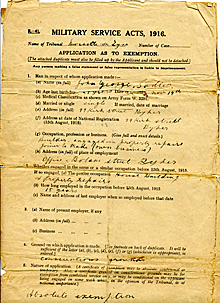

In the light of the impasse between Jack’s 'absolutism' and the authorities’ offer of the Home Office Scheme as the only way out, Jack served out his sentence. On release, he was returned to the Army, again ordered to put on uniform, again refused, again court-martialled and sentenced to two years hard labour, again commuted to six months. On his second release, the cycle began for the third time, when Jack decided to try another route. Using the argument that the legislation gave power to a Local Tribunal to rehear an application, provided that there was new evidence, and citing the findings of the Appeal and Central Tribunals as new evidence, in conjunction with his own integrity in having knowingly incurred two prison sentences and now being liable to a third, he sought such a rehearing by a letter dated 12 October 1917, covering the official application form.

Application for rehearing by Newcastle Local Tribunal

In his formal application Jack referred to the covering letter, stating his 'absolutist' stance as the reason for his objection. It appears unlikely that the Newcastle Tribunal granted Jack a rehearing, no doubt arguing that the Appeal and Central Tribunals were rehearings enough; certainly his legal status was not changed, and his third Court-Martial and conviction took their normal course.

Hunger-strike temporary discharge notice

The length of Jack’s third prison sentence is not known, but it seems to have been two years, this time without being commuted. Certainly Jack was still in Newcastle prison in early 1919. In the meantime, Jack had determined upon another tactic, also used by some other COs - hunger strike until either death or release. This tactic was in conscious imitation of some suffragettes of the immediate pre-1914 period, and the response of the authorities was similar. In order to avoid both the potentially damaging effects of forcible feeding, and the scandal of deaths in prison, legislation passed in 1913 for the sake of the suffragettes was brought into play. This enabled a hunger-striking prisoner to be temporarily discharged well before the point of the death, but required to return on a date when health would be deemed to be restored (the period of ‘sick leave’ not counting towards the sentence). This notice authorised Jack’s temporary discharge from Newcastle Prison from 5 March until 3 April 1919.

Parliamentary Comment in North Mail, 11 March 1919

Despite a general bias in the Press and Parliament against the position of COs, there were several concerned MPs and peers who regularly asked questions or made comments on their behalf. Interestingly, as this press cutting shows, one of this group was himself a retired colonel, and one of the issues he raised on 10 March 1919 concerned specifically the 11 COs in Newcastle Prison who had begun their hunger strike on 16 February. Before Jack’s temporary release on 5 March he and the others had been forcibly fed by the insertion of a rubber tube in the mouth extending to the stomach, through which liquid nourishment was poured. As to suggestions of mistreatment, the Home Secretary responded, 'The conscientious objector has not done what the average man in this country considers to be his duty to his country… Every man in prison today has been found not to have such a conscientious objection as would entitle him to total exemption'.

Letter from No-Conscription Fellowship re discharge from prison

By the spring of 1919 not only was the First World War effectively over, after the Armistice of 11 November 1918, but conscription was being wound up, troops were beginning to be demobilised and parallel measures were needed for COs. It was ordered in April 1919 that all COs still in prison who had already served at least 20 months would have their sentences commuted to time served. This circular letter from the N-CF, dated 17 April 1919, kept Jack informed of the N-CF’s representations to the authorities on the matter – an example of the many ways in which the N-CF both helped COs directly and campaigned on their behalf. The letter indicates that Jack was still at home, although according to his temporary discharge notice he was due to return to prison on 3 April; he claimed extended ‘leave’ because his health had not yet recovered, and he was ultimately discharged without ever returning to prison.

Instead, he married his fiancée, Margaret, who had supported him throughout, on Easter Monday, 21 April 1919, and they honeymooned in Scotland.

Army discharge certificate

Even though Jack was finally discharged from prison in or about April 1919, he was still legally a 'soldier', without his ever having performed a useful function for the Army since formal enlistment on 6 November 1916. Eventually he was discharged in his absence on 16 June 1919 on the grounds of 'misconduct', with a warning not to attempt to re-enlist without disclosing the circumstances of his discharge – on pain of two years Hard Labour!

Unsurprisingly, Jack never returned to the Army, but he did return to prison. In the Second World War he was imprisoned for a month for refusing to arrange fire watchers at his business – not because he did not believe in protection against bombing, but because he refused to do it as part of the machinery of the warfare state: the 'absolutist' position he shared with his two brothers in the First World War, and with his son-in-law and his son-in-law’s brother, both of whom were imprisoned as conscientious objectors in the Second World War. Jack died in 1961.

|