|

|||

| BACK |

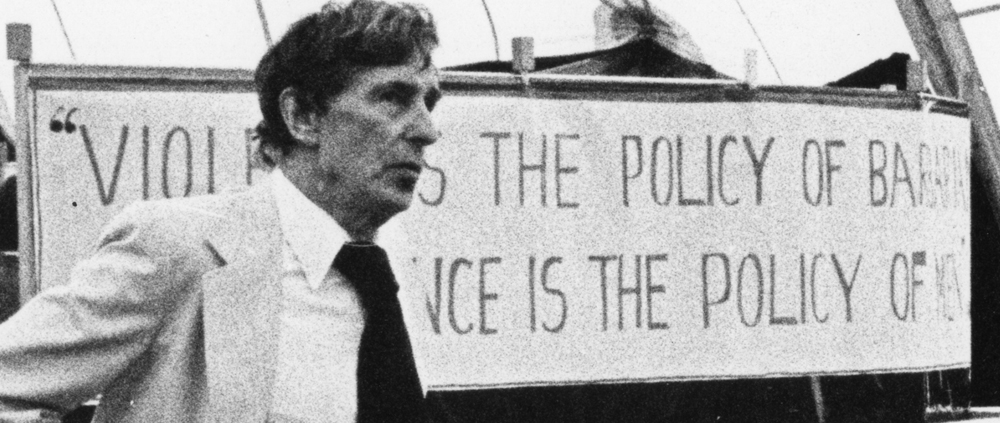

Michael Tippett speaking at a PPU exhibition |

||

MICHAEL TIPPETT Michael Tippett, President of the Peace Pledge Union, died on 8 January 1998, six days after his 93rd birthday. He has been rightly celebrated throughout the media for his notable contribution to the music of this century, but less attention has been paid to his contribution to pacifism, which he once described in relation to himself as ‘almost deeper than the music’. Michael was aged nine at the outbreak of the First World War, and like many children, was affected by the fervour for the war without understanding it fully. He was sufficiently moved, however, to refuse at the age of 13 to join the Officer Training Corps at Fettes College. Later he was increasingly disappointed by the failure to realise the aspirations for which the war had supposedly been fought, and in common with many idealists of the period, he briefly joined the Communist Party. He left when he failed to convert his local branch to Trotskyism, and joined the Musicians’ Group of the Militant faction in the Labour Party. He wrote a play War Ramp, confronting the conflict of political idealism and pacifism, which was performed at Labour Party rallies. After seeing in a newsreel the endless rows of little crosses in Flanders, he ‘knew I must work towards a climate in which repetition of such brutalities would never be accepted’. Disillusioned with party politics, Michael joined the Peace Pledge Union in 1940. The Second World War became seminal to his reputation both as a pacifist and as a composer. In June 1943, whilst Director of Music at Morley College, London, he refused the condition of his conscientious objection Tribunal that he should undertake full-time civil defence, fire service or land work, arguing, with the non-pacifist support of Ralph Vaughan Williams as a witness, that music was his most constructive contribution to society. He was sentenced to three months imprisonment. If his pacifism was unacceptable in society, he later commented, ‘When I entered Wormwood Scrubs it was really as if I had come home’. At the same time he was aware of the ultimate price of pacifism paid by his contemporaries on the other side of the war: ‘If I had been in Germany, I would have been shot’. The first performance of his Concerto for Double String Orchestra was given at the Wigmore Hall in July, when ‘circumstances beyond his control prevented the composer from attending’, as the Conscientious Objectors’ Bulletin put it. He was rehearsing the Scrubs orchestra, whose involved ‘prison politics’ did not hinder him from feeding a comrade on bread-and-water punishment. He also had the pleasure of a visiting performance by Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears, fellow musicians and conscientious objectors, at which he was invited on to the platform, against the normal rules, on the pretext that someone was needed to turn the pages. Ben and Peter entertained Michael to breakfast immediately upon his release, and a celebratory performance of his Second Quartet was given at Wigmore Hall later in the day. Meanwhile, in direct response to Kristallnacht, the November 1938 pogrom against Jews, which had been claimed as justified by the shooting of a German diplomat in Paris, Michael had begun, two days after the British declaration of war, to compose the oratorio A Child of Our Time, as ‘an impassioned protest against the conditions that make persecution possible’. The work was completed in 1941, first performed in March 1944 at the Adelphi Theatre, London, and was the beginning of Michael’s prominence as a rising composer. In July 1944 Peace News published a short pamphlet by Michael, Abundance of Creation, in which he argued that ‘If a pacifist has to contract out of an intolerable social condition, he needs to sense that he is contracting in to something more generous...we are only able to contract out of war into peace’. The text was reprinted in Michael’s volume of essays Moving into Aquarius (1974), with a brief introduction commenting, ‘My own conviction is based upon the incompatibility of the acts of modern war with the concept I hold of what man is at all’. The Second World War over, Michael began to take an active part in the pacifist movement. He served on PPU Council 1947-51, when he warned ahead of others against misinterpretation of the pacifist position if the PPU associated too closely with the World Peace Council, a perennial apologist for the Soviet bloc. He was PPU Chair 1955-57, and also a Director of Peace News, to which he contributed from time to time. In 1958 he was elected honorary President of the PPU, which post he continued to hold at his death. State honours, including a knighthood and the Order of Merit, did not inhibit him from recording his imprisonment in his Who’s Who entry. He interrupted his increasingly busy schedule of composition and performance to talk to PPU meetings (the latest occasion was the PPU’s 50th anniversary celebration in 1984), when he spoke not only about the relationship between the creative artist and humanity, but also about current problems such as civil rights, race relations, latter day wars and the nuclear threat. Michael’s last significant contribution to the movement was in 1994, when, having headed the financial appeal, he made a particular effort at the age of 89 to unveil in Tavistock Square, London, the Commemorative Stone to conscientious objectors all over the world and in every age. As Michael said to the PPU AGM in 1966, in his gentle, disarming way, ‘In my walk of life we do grow old, but in some ways we seldom retire...as you grow older so the demands accumulate’. We remember him with gratitude for his music, but above all for his enduring witness for peace.

Read: Moving into Aquarius |

'In the poetry for the Third Symphony, I included a line which I had been ‘forced’ to write: “My sibling is the torturer”. It is a frightening line, and I do not know that I understand what it means. And yet I know instinctively that it is something that we have got to face up to; there is some element, which we have not yet understood, about why people do things in this violent form. I am afraid that unless we make some definite effort to understand we shall not get ourselves round this corner. My emotional responses in favour of the victims of war and in opposition to notions of military heroism do not necessarily make me a better person than the ‘heroes’. Individual Responsibility, Talk at PPU AGM

|

|

Peace Pledge Union, 1 Peace Passage, London N7 0BT. Tel +44 (0)20 7424 9444 contact | where to find us |