|

|

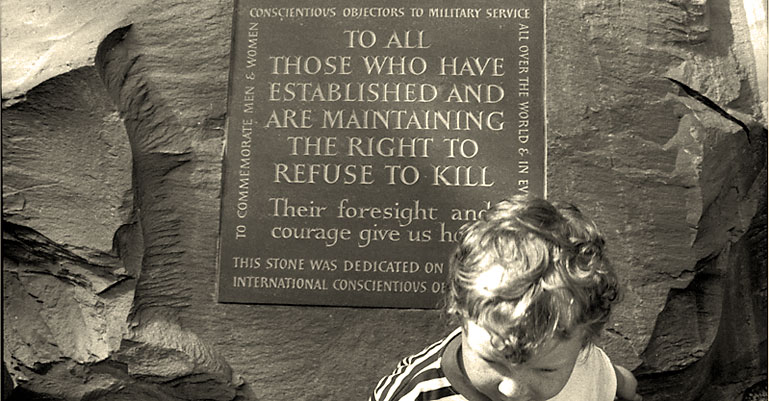

| Conscientious objection stone Tavistock Sq London |

| Leonard Bird's story | |

Leonard was at first refused exemption, but was granted it after appeal on condition that he did alternative work. He refused. 'I took the view that if we oppose war we oppose all war. If you're doing useful work in civilian life, war's no reason for changing what you're doing - if it's not useful, you ought to change it anyway, not simply because there's war service attached to it.' In fact Len could have evaded call-up in a number of ways. He was a long-term law student; his firm needed him because other staff had been called up; while doing office work part-time he could also have worked in a hospital (where one of the firm's partners was chairman of the board). In addition, another partner, the brigadier, was in charge of air-raid defence in the south Midlands. 'He told me, "When you get all that CO nonsense out of your head, you come and work for me".' But Len wouldn't compromise, and went to prison instead. Len believed he was among the first COs to be imprisoned for not complying with the terms of his exemption. He was given a year's sentence by 'a very hard-faced magistrate'. He was, however, released before the year was up, still faced with the order to do alternative service. 'I did voluntary firewatching when I was working in the firm of solicitors, but when it was a compulsory requirement and I'd not got exemption from that, I refused to do compulsory firewatching. I got prosecuted four times and sent to prison two more times.' The Home Office had issued a regulation saying that CO prisoners should not be given 'war work'. However, Len discovered that war work was what the prison governor had assigned him to do. So he went on strike. Bread and water, solitary confinement, and extra time were among his punishments. He sent a petition to the Home Office, 'but of course somebody up there threw it in the wastepaper basket and said it wasn't applicable'. He was, however, sent to a new work department where the officer in charge was more sympathetic. 'Some of the officers were terribly antagonistic, but one or two were understanding. One of them got to learn a bit about us when we argued with him, and he began to treat us quite reasonably.' In prison Len met ex-soldiers, there for 'committing a small theft or hitting a policeman on the nose. We knew they'd done it so they could avoid being sent abroad on active service. We had very little trouble and very little argument. We had more argument with the chaplain who didn't understand us when we asked him what "praying for our enemies" could mean. 'Prison is a terrible experience. Anyone that says it's a holiday camp or home from home doesn't know what they're talking about. It's terrible to be away from your home and terrible to be away from your work or your friends and everything you know. It's such a horrible experience that you tend to make light of it; of course, you'd die a quick death if you didn't. I remember the first day I came out I was terrified at the pace at which the buses were going. 'But I would do it again. When I was coming out the first time one of the senior officers turned to me and said "Do you feel any different now to what you felt when you came in?" And I said "Yes, I do". And he slapped his thigh and said, "There you are, I knew we'd altered you. How different do you feel?" And I remember saying, "When I came in I thought I was right. Now I know I was." It seems to me that people generally have got to realise that war just has no place in modern society. There are other methods of solving your difficulties.' Len did eventually work on a farm, and was the Peace Pledge Union's North of England organiser. After the war he was a solicitor, became chairman of the PPU, and continued his peace work for the rest of his life. | continue |

World War Two - Britain - INDEX |

| menwhosaidno.org |