|

|||

| BACK |

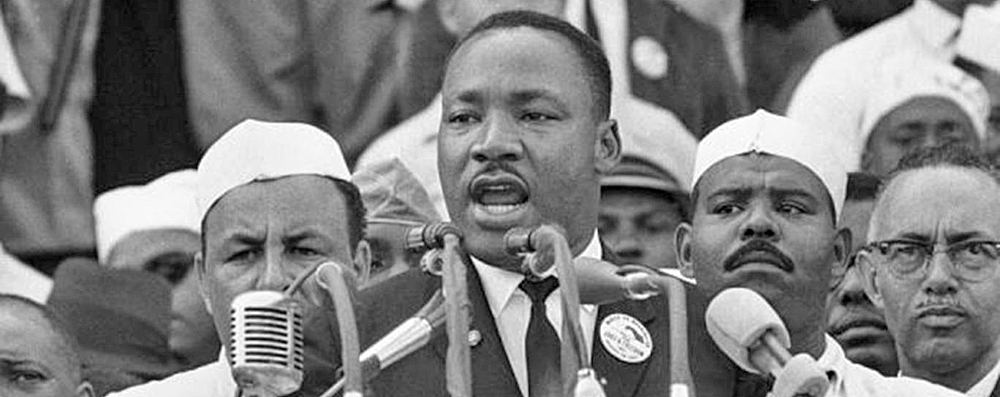

MARTIN LUTHER KING The 1964 Nobel Peace prize was given to Martin Luther King, Jr., who was, after Ralph Bunche, the second black American to win the award. He was, said Chairman Jahn of the Nobel committee, ‘the first person in the Western world to have shown us that a struggle can be waged without violence. He is the first to make the message of brotherly love a reality in the course of his struggle, and he has brought this message to all men, to all nations and races’ King was born Michael Luther King, Jr., the second child and first son of a Baptist minister in Atlanta, Georgia. When the boy was six years old, two white playmates were told not to play with him, and his mother had to explain about segregation: it was a social condition, and he was as good as anyone else. The father lifted the boy's vision higher: he told him about Martin Luther, the great leader of the Reformation, and said that from now on they would both be named after him. Martin Luther King, Jr., a very bright student, began to show his oratorical ability as early as his high school years. At fifteen he entered Morehouse College in Atlanta, the distinguished black institution, and decided to become a minister. As he said later, ‘I'm the son of a preacher . . . my grandfather was a preacher, my great-grandfather was a preacher, my only brother is a preacher, my daddy's brother is a preacher, so I didn't have much choice.’ During his senior year, when he was eighteen, King was ordained and elected assistant pastor of the Ebenezer Baptist Church, which had been established by his grandfather and where his father was then the minister He graduated at nineteen in sociology and went on to Croziet Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, where he was one of only six black students in a student body of about one hundred. In three years he received the degree of bachelor of divinity, having been president of the senior class and valedictorian. With a Crozier fellowship, he entered Boston University in 1951 to study for the doctorate. While at Crozier he first heard of Gandhi's nonviolent movement that had won independence for India, and he began to think of how such methods might be used by the black people in America. It appeared to him that Gandhi ‘was probably the first person to lift the love ethic of Jesus above mere interaction between individuals to a powerful effective social force on a large scale.’ In his studies at Boston University, King was introduced to the leading theological ideas of the day, and he also had the opportunity to follow philosophy course at Harward. In Boston he met the beautiful and talented Coretta Scott, who was studying to be a concert singer at the New England Conservatory of Music, but who gave up her career to become his wife. They were married in 1953 and were to have four children. Coretta was always a great support for him, and after his death she carried on his work, becoming a national leader in her own right. In 1954, after King had completed the course work for his Ph.D., he had job offers from colleges and churches in the North, but he felt that his place was in the South, where he could do more for his people. When he decided to answer the call from Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, however, Coretta had reservations. She had grown up in Alabama only eighty miles from there, and she knew that Montgomery was still living in hallowed memories of its past as the first capital of the Confederacy and that they would encounter deep racial prejudices. Later she came to feel that the choice of Montgomery ‘was an inevitable part of a greater plan for our lives.’ King officially entered upon his pastor's duties in Montgomery in September 1954. The next year he received his Ph. D. from Boston University, in November their first child was born, and a few weeks later the series of events began in Montgomery that propelled him into a greater role than he could ever have foreseen. On 1 December 1955, Rosa Parks, a forty-year-old seamstress, refused to give up her seat in a bus to a white man as she was ordered to do by the driver. ‘I was just plain tired, and my feet hurt,’ she explained later. For this she was arrested and charged with disobeying the city's segregation ordinance. The black community was outraged, and their pastors quickly organized a one-day boycott of the buses in protest. This was so successful that it was decided to continue the boycott until demands to desegregate the buses were met. For leadership the pastors turned to their young colleague of the Dexter Avenue Church, who had already won a reputation among them for his powerful preaching. They felt that he had not been in town long enough to make enemies and could easily relocate to another city if things went wrong. Consequently, Martin Luther King, Jr., became president of the committee to conduct the boycott, which was hopefully called the Montgomery Improvement Association. He was then not quite twenty-seven. In his first speech, to a mass meeting on 5 December, King announced the nonviolent principles that were to guide the civil rights movement from then on. In the struggle for freedom and justice to which they were called, he said, ‘Our actions must be guided by the deepest principles of the Christian faith.’ He concluded: ‘If you will protest courageously, and yet with dignity and Christian love, future historians will say, ?There lived a great people - black people - who injected new meaning and dignity into the veins of civilization.? This is our challenge and our overwhelming responsibility.’ In this spirit the boycott effort persisted, despite bitter efforts to break it through all kinds of harassment, abuse, and persecution. For over a year the black community of Montgomery stayed out of the public buses, walking, car-pooling, and using all possible means of transit, until finally the United States Supreme Court ruled that segregation on the buses was unconstitutional. King was the target for arrests, constant anonymous death threats, and a night-bombing of his home. The Montgomery bus boycott drew worldwide attention to the racial struggle in the South and to King. The movement for racial justice spread beyond Montgomery, and King became the leader of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which coordinated the major civil rights activities. Throughout the South blacks rallied at King's call, fighting segregation through marches, demonstrations, sit-ins, and other nonviolent methods. King was always at the forefront, and he was beaten, arrested, and jailed. In one prison cell he wrote his moving ‘Letter from a Birmingham Jail,’ explaining to some white ministers who counseled patience ‘why we can't wait.’ He traveled thousands of miles, in the North as well as in the South, making speeches, raising money, appealing for support from political, labor, and business leaders. In 1963, when 250,000 persons, 75,000 of them white, took part in a march in Washington to urge Congress to pass civil rights legislation, King addressed them from the Lincoln Memorial in his most famous speech, ‘I Have a Dream,’ presenting his vision of an America living out the true meaning of its egalitarian creed. Great steps forward were taken when Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, but realization of the dream was still far off. King had not sought the leadership in Montgomery, but felt that God had directed him to take it on, and in the following years he continued to feel that he had no choice, despite the pain and suffering he endured. He sometimes thought wistfully of a peaceful life in a teaching post somewhere, but he put such thoughts aside. The public commendation that he received only drove him to devote more of his energies to the cause he served. He lived with danger and had premonitions of an early death, but he carried on, firm in the faith that he was meant to. Early in 1964 King learned that he had been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by Swedish parliamentary deputies, and in the summer a request came from Oslo for documentation, indicating that his candidacy was being seriously considered. Possibly with an eye on the prize, arrangements were made for King to have an audience with Pope Paul VI and to visit West Berlin in September. But King expected that the award would be given to someone who was involved with international peace activities. He returned from Berlin exhausted and checked into a hospital for a physical examination, mainly for a few days rest. The next morning Coretta telephoned to wake him up with the news that he had won the prize. Sleepily, he thought he was still dreaming. Once awake, he called a press conference at the hospital, but first met with his wife and closest associates, explaining to them that the prize represented the international moral recognition of their whole movement, not his personal part in it. He asked them to join him in prayer for strength to work harder for their goal. At the press conference he announced that he would give the prize money of approximately fifty-four thousand dollars to the movement, which he arranged to do on his return from Oslo. Feeling that the award had been won by them all, King took with him to Oslo a number of the other leaders, and the party of thirty represented the largest group that had ever accompanied a prizewinner. Coretta remembers that they had quite a time getting her husband into his formal dress for the ceremony. He bridled especially at the ‘ridiculous’ ascot tie, vowing ‘never to wear one of these things again.’ He never did. All the same, King cut a handsome figure when he stepped to the rostrum to deliver his speech of acceptance, at thirty-five the youngest of all those who had received the prize. He was shorter than the audience had imagined, but as his rich baritone filled the hall with its throbbing cadences, he grew taller in their eyes. He declared that he was accepting the award on behalf of the civil rights movement, considering it ‘a profound recognition that nonviolence is the answer to the crucial political and racial questions of our time - the need for man to overcome oppression without resorting to violence and oppression.’ He continued: Civilization and violence are antithetical concepts. Negroes of the United States, following the people of India, have demonstrated that nonviolence is not sterile passivity, but a powerful moral force which makes for social transformation. Sooner or later all the peoples of the world will have to discover a way to live together in peace, and thereby transform this pending cosmic elegy into a creative psalm of brotherhood. If this is to be achieved man must evolve for all human conflict a method which rejects revenge, aggression and retaliation. The foundation of such a method is love....I accept this award today with an abiding faith in America and an audacious 0th in the future of mankind. In his Nobel lecture King said that the most pressing problem confronting humanity today was ‘the poverty of the spirit which stands in glaring contrast to our scientific and technological abundance.’ This was apparent in the three evils that had grown out of man's ‘ethical infantilism,’ racial injustice, poverty, and war, which were all intertwined. Nonviolence ‘seeks to redeem the spiritual and moral lag . . . to secure moral ends through moral means.’ It was a ‘weapon unique in history, which cuts without wounding and ennobles the man who wields it.’ Jahn had already cited King's earlier statement that ‘the choice is either nonviolence or nonexistence.’ Now King emphasized that peace was a positive concept and called for ‘an all-embracing and unconditional love for all men. When I speak of love, I am speaking of that force which all of the great religions have seen as the supreme unifying principle of life. Love is somehow the key that unlocks the door which leads to ultimate reality’ King left Oslo with a new and overwhelming sense of what the world was expecting of him. At his hero's welcome in New York he expressed his own intensified feeling of personal responsibility in speaking of individuals who ‘will hold the torch firmly for others because they have overcome the threat of jail and death. They will hold this torch high without faltering because they have weathered the battering storms of persecution and withstood the temptation to retreat to a more quiet and serene life’ After Oslo, King attacked more vigorously all three of the evils of which he had spoken. He took a public stand against the American war in Vietnam, antagonizing political leaders who had helped with civil rights legislation and alienating former associates who thought he should keep to the one issue. He lobbied for federal assistance to the poor, insisting that the misery of poverty knows no racial distinctions, and he planned a ‘Poor People's March’ on Washington for 20 April 1968. He was not to live to see it. On 4 April, while in Memphis, Tennessee, helping striking garbage workers, Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated. Only a few months before, in a sermon at Ebenezer Baptist Church, he had spoken of his own death and funeral. He wanted no long eulogy: Say that I was a drum major for justice. Say that I was a drum major for peace. That I was a drum major for righteousness. And all of the other shallow things will not matter. I won't have any money to leave behind. I won't have the fine and luxurious things of life to leave behind. But I just want to leave a committed life behind. In 1986, by act of Congress, the United States began the annual celebration of the birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr., in January as a national holiday.

|

'I have a dream that my little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character.'

Dual function CD features a selection of materials on King’s life and his work for peace. Listen to his speeches on a CD player or find much more using a computer. The CD includes lessons for students and background for teachers. Suitable for KS3 classes through to A level. This is an invaluable resource is invaluable for the study of human rights, prejudice and peaceful responses to conflict in Citizenship, History and RE classes. | more |

|

Peace Pledge Union, 1 Peace Passage, London N7 0BT. Tel +44 (0)20 7424 9444 contact | where to find us |