| HOME | TRIBUNAL HOME |

With the resignation of A. Barrett Brown at the end of June, the National Committee of the NCF was resolved to pour additional energy into campaigning for the rights of imprisoned Conscientious Objectors. The July issues of The Tribunal reflect this rediscovered focus.

5th July Issue

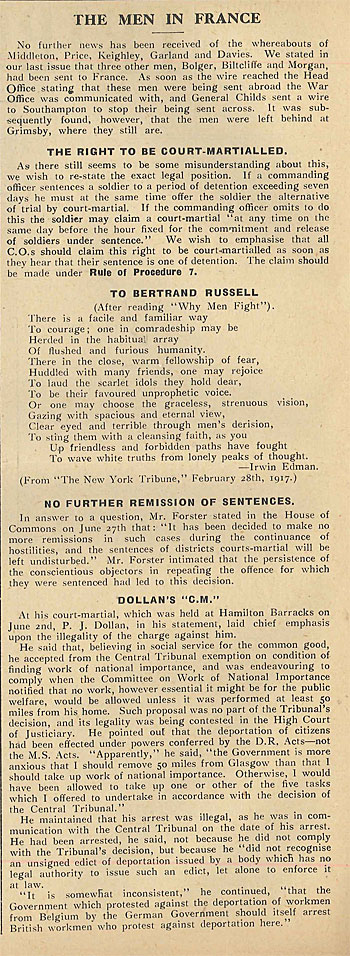

The first issue of The Tribunal in July 1917 follows on this theme of concentrating on the experiences of individual Conscientious Objectors and is  packed with reports on the treatment of individuals, prison conditions and news from the Home Office Camps. In reports from around Britain and France, The Tribunal paints a picture of COs on the receiving end of the now typical military brutality and government incompetence. NCF men reported from guardhouses of callous treatment, work strikes were sporadically cropping up in prison after prison, tribunals continued their ignorant and illegal work under the military service act and the civil government ruled that there would be no remission of sentences passed down to COs.

packed with reports on the treatment of individuals, prison conditions and news from the Home Office Camps. In reports from around Britain and France, The Tribunal paints a picture of COs on the receiving end of the now typical military brutality and government incompetence. NCF men reported from guardhouses of callous treatment, work strikes were sporadically cropping up in prison after prison, tribunals continued their ignorant and illegal work under the military service act and the civil government ruled that there would be no remission of sentences passed down to COs.

Amidst these sadly almost day-to-day difficulties, another more troubling development dominated the issue. Another group of Absolutist COs were being readied for transport to France in a sinister echo of 1916’s “Frenchmen” scandal. Eight COs formally in the NCC, undergoing short periods of punishment after court martial, looked to be taking the same route as the 30-40 shipped over the previous year - transportation to a battle zone, and much harsher punishments. Though Army Order X ostensibly protected COs from such treatment, men on sufficiently short sentences after court martial remained in the hands of the military.

Happily for the COs involved, the NCF’s political connections were, by this time, solid enough to quickly swing into action. “As soon as the wire reached the Head Office stating that these men were being sent aboard” the July 5th Article states “the War Office was communicated with, and General Childs sent a wire to Southampton to stop them”. Such a remarkably quick response to CO related issues in the War Office would have been unthinkable in 1916 and is a testament to the dogged nature of the NCF. Through tireless lobbying and campaigning, as well as simply through having the best and most comprehensive information on COs, they had managed to position themselves as the representatives of the CO community. Their demands would largely be resisted, but their voice was most certainly heard.

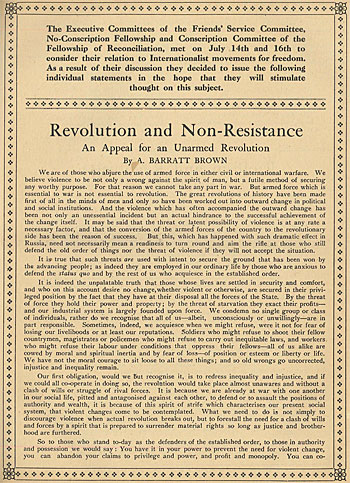

19th July 1917 - Executive Committee Supplement

The July convention of the committees of the Friends Service Committee, No-Conscription Fellowship and Fellowship of Reconciliation met to “consider their relation to internationalist movements for freedom” and published a significant supplement in the 19th July issue of the Tribunal. We commonly think of a division between the religious and political sides of the pacifist movement during the war, but the division was less significant than it often seems. While the NCF was non-sectarian it was undoubtedly socialist and political in character, while the FSC and FoR were religious movements, they also had a firm grounding in socialist and internationalist politics.

The jointly issued statements are socialist and internationalist in nature, and relentlessly, endearingly optimistic. A. Barratt Brown, in what was probably one of his last appearances officially representing the National Committee of the NCF, did not call for restraint in political action, but for “an unarmed revolution” to end domestic and international political strife. Acknowledging that violence has always been the traditional method of defending the gains won by revolution, Barratt Brown instead calls for a revolution through cooperation, non-resistance and political action.

Bertrand Russell, in another statement that could well have been issued straight from the pages of The Tribunal supported this position, that there “is no need of violence in order to bring the reign of violence to an end”. In the event of failure to bring about revolution, Russell tellingly warns that “The successes of revolution depends always upon the power of new ideas over men’s minds. The old ideas, which have dominated governments hitherto, have issued in the war, and will lead to new wars in the future if they continue to be believed”.

The statements issued by Edith Ellis for the Friends Service Committee and Henry Hodgkin for the Fellowship of Reconciliation are no less revolutionary. While both statements refer to “God our Invisible King”, the tone of both is markedly socialist, calling for both peace, pacifism and a new politics that would ensure both. “A new social order, based on equality, trust and co-operation” that eschews war as “not only a bad way of achieving our ideals, but no way”, is the rule of the day.

Again, as in previous months, the influence of the February revolution in Russia is clearly seen in these statements. They look forward beyond the situation in 1917 to a better and more peaceful world, and one that appeared, in all likelihood to be within reach.

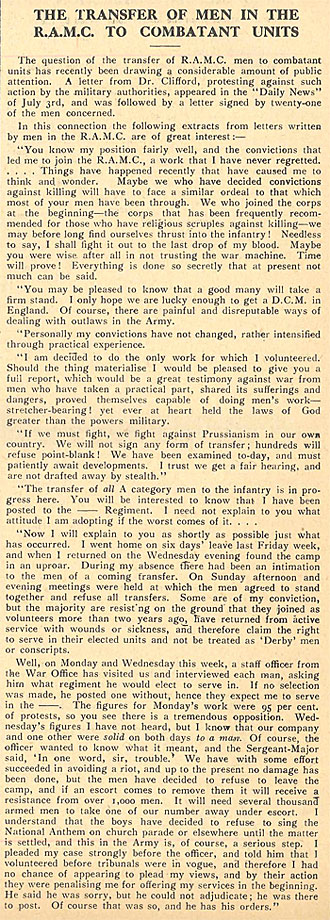

26th July - RAMC and Combatant Units

As the NCF focused itself more on the experiences of Conscientious Objectors, developments in France and Egypt widened the scope of what it meant to be a CO.  With the demand for more men ever more pressing due to continuing military deadlock, the British Army scrabbled to convert it’s thousands of non-combatant volunteers into combatant soldiers.

With the demand for more men ever more pressing due to continuing military deadlock, the British Army scrabbled to convert it’s thousands of non-combatant volunteers into combatant soldiers.

In this case, the Army sought to plunder the volunteers of the Royal Army Medical Corps and turn them from medical support to frontline soldiers. All “Category A” men, the fittest and most capable, in the RAMC were to be forcibly transferred to combatant units. As the RAMC was a non-combatant organisation, many of the men who had volunteered in the days before Conscription were as dedicated to principles of non-violence as the Absolutist COs in prison. With no recourse to a tribunal, or to representation as a CO - or even a method of being recognised as an objector to combatant service, the RAMC volunteers were in a precarious position.

The most galling part of this scheme would have been the realisation that to the Army, the years of volunteer service the RAMC non-combatants had gone through meant little. Religiously, Politically and Morally, these men had refused to take life, but had resolved to save it, volunteering to do so long before conscription. To attempt to force them to take life now was, in the words of one man quoted in the article “penalising me for offering my services in the beginning”.

With the knowledge of the effectiveness of CO resistance in Britain and fully aware they “will have to face a similar ordeal to that which most of your men have been through”, the RAMC men prepared to resist this attempt to force them to compromise their principles. Through work strikes, outright refusal and solidarity within their ranks, the RAMC volunteers would be able to largely stand united against the machinations of the Army, but their stand was not without difficulty - and will be covered as it was reported in the pages of the Tribunal.