| HOME | TRIBUNAL HOME |

February 1919

For the CO movement, these first months of 1919 were a holding pattern - and one that was becoming unbearable. Held in prison - with no suggestion of forthcoming release - or still on Home Office Camps, kept in Work of National Importance, or refused an early demobilisation from the NCC, change seemed tantalisingly close, but still impossibly distant. This sense of waiting, of tension between present and future, fills up the four issues of the Tribunal in February 1919.

CO Deaths in February:

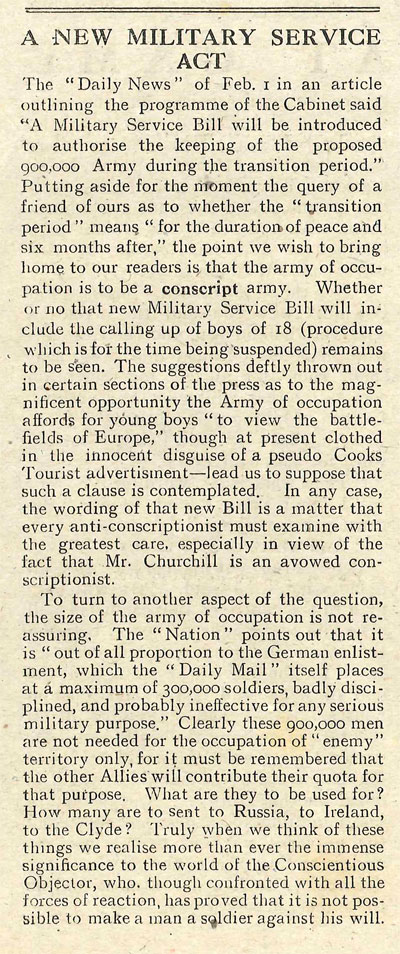

6th February: A New Military Service Act

Though waiting for release, there was still plenty of scope for the situation to get worse. “A New Military Service Act” covers a rumour that was all too readily believable for Conscientious Objectors and their supporters - the extension of Conscription post-war. The report that the “programme of the Cabinet” was to continue conscription to meet the Army’s requirements post-war, sending conscripts to the Army as part of the British Occupation of the Rhine, must have been all too believable to COs. It was a clear sign that Conscription was not necessarily tied to the current conflict. Conscription in peacetime was a naked threat of social control, as Objectors and sympathisers well knew, and the editorial asks “What are they to be used for? How many are sent to Russia, to Ireland, to the Clyde?”. The possibilities for conscript armies were threatening - the continuing “Intervention” in Russia, the escalating conflict in Ireland, but perhaps most sinister of all, the Clyde - to put down workers striking for better conditions.

All of this turned out to be a rumour - the British Army of the Rhine would be comprised of voluntary detachments, the last conscript being sent home in 1920, and conscription was not extended into peacetime. But the wariness and fear are understandable. Not just as a stand against the immorality of conscription, but in a very specific sense. If the Military Service Act was to remain in place, however modified, for peacetime use, what did this mean for the release of COs? How many more men would be called up and refuse, and would COs imprisoned during the war be kept inside during peace as well? In a month of tension, these questions found no comfortable answers.

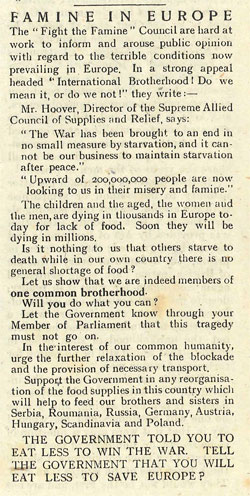

13th February: Famine in Europe

Looking ahead did not always mean worry about the future of conscription and of the conscientious objectors who had defied it, but also working constructively for a better future. Many COs and supporters would finish the war period working for or with aid agencies, attempting to undo some of the damage inflected on men, women, children and whole communities by the conflict. “Famine in Europe” is both an appeal and a news item, covering the developing (and ever worsening) famine in Germany, Central and Eastern Europe. The “Fight the Famine” Council (which would later become Save the Children), was rapidly organising systematic relief to families in Germany and Austria, vainly attempting to rail against the ongoing blockade of Germany which was costing thousands of lives.

For the Tribunal, long since supporters of equitable post-war treatment and reconstruction, such a campaign would have appealed on several grounds. Charitable work to save lives would be self-evidently supported, and a push to end the deliberate decision to starve the people of Germany into submission - and soon, starve them to death, had featured in the Tribunal since mid 1917. It’s also indicative of a wider theme running through the newspaper in the early months of 1919, a return to a world configured away from war. It was not enough to end the war and retain the same militaristic mindset that could so easily lead to aggression and conflict. Instead, a move to remove all the lasting effects of war, the legal , moral and economic conditions that had created and sustained it, meant creating peace and removing possible causes of another. The fact that “the war has been brought to an end in no small measure by starvation” was reason enough that it “cannot be our business to maintain starvation after peace”.

For the Tribunal, long since supporters of equitable post-war treatment and reconstruction, such a campaign would have appealed on several grounds. Charitable work to save lives would be self-evidently supported, and a push to end the deliberate decision to starve the people of Germany into submission - and soon, starve them to death, had featured in the Tribunal since mid 1917. It’s also indicative of a wider theme running through the newspaper in the early months of 1919, a return to a world configured away from war. It was not enough to end the war and retain the same militaristic mindset that could so easily lead to aggression and conflict. Instead, a move to remove all the lasting effects of war, the legal , moral and economic conditions that had created and sustained it, meant creating peace and removing possible causes of another. The fact that “the war has been brought to an end in no small measure by starvation” was reason enough that it “cannot be our business to maintain starvation after peace”.

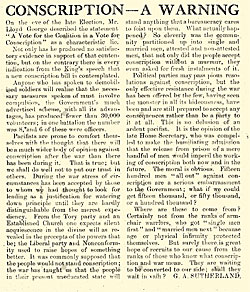

20th Feburary 1919: Conscription - A Warning

Following on from December 1918’s Election, the new Coalition Government set out its policies for the year ahead in the King’s Speech on the 11th of February. To COs and supporters, it seemed to indicate that “a new conscription bill is contemplated”. Lloyd George in his election campaign had refuted that “A vote for the Coalition is a vote for Conscription” - but how far could he be trusted?

“Conscription - A Warning” is a realistic warning not to count on the widespread support that many anti-war activists felt was now their due. With war exhaustion and widespread casualties seemingly setting up a perfect base for support for anti-war movements after the war, the article claimed that “Pacifists are prone to comfort themselves with the thought that there will be a much wider body of opinion against conscription after the war”. The warning comes against complacency, reminding readers of the divide and rule tactics that were used to systematically remove religious, trade unionist and parliamentary opposition to Conscription in the run up to it’s introduction.

“Conscription - A Warning” is a realistic warning not to count on the widespread support that many anti-war activists felt was now their due. With war exhaustion and widespread casualties seemingly setting up a perfect base for support for anti-war movements after the war, the article claimed that “Pacifists are prone to comfort themselves with the thought that there will be a much wider body of opinion against conscription after the war”. The warning comes against complacency, reminding readers of the divide and rule tactics that were used to systematically remove religious, trade unionist and parliamentary opposition to Conscription in the run up to it’s introduction.

But the article is not simply a warning. The system of conscription relied on acceptance and consensus, not overwhelming support. The Government “had to make the humiliating admission that the release from prison of a handful of men would imperil the working of conscription both now and in the future”. So their stand from 1916-1919 had the effect of weakening the conscriptionist system, and what could be done in the future? “Fifteen hundred men “all out” against conscription are a serious embarrassment to the Government; what could we do if we could get 15 thousand, or fifty thousand, or one hundred thousand?”

New recruits to the cause would not come easy - and should not be taken for granted. Hard and constant work could win over the masses; “surely there is a great hope of recruits to our cause from the ranks of those who know what conscription and war mean. They are waiting to be converted to our side; shall they wait in vain?

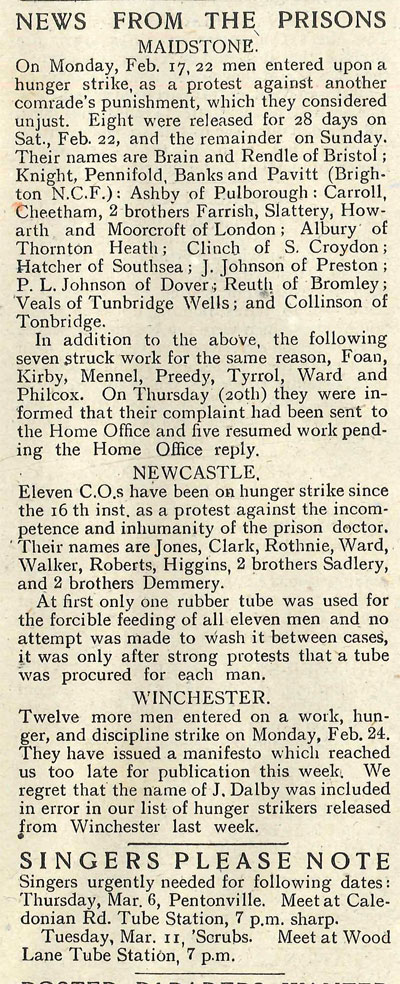

27th February 1919: News from the Prisons

While the Tribunal and movement as a whole looked forward to the future and worried about release, Absolutist COs in prison went about trying to secure it for themselves. News from the Prisons sees men push themselves to the limits of medical discharge, both in protest and to secure an early release. Dedicated, now vindicated, Absolutist COs languished in prison and were now certain of eventual release - but when?

COs in Maidstone, Newcastle and Winchester are covered in this article - and the article itself is (shockingly, for monthly reviews of the story of COs) one of the first we’ve covered on the story of individual men for some time. The situation in prison had been static since November 1918, and though the Tribunal had consistently covered their experiences, less and less of the paper had been given over to following individual stories. This phase of the Absolutist story was coming to an end - hunger, work and discipline strikes were to dominate the lives of COs in prison until final release came in the summer.

Hunger and work strikes allowed men a way of registering their disgust with continuing imprisonment, and could, at this late stage of the war, secure release. Eventual discharge under the Cat and Mouse Act may have been intended to be temporary until a CO recuperated, but many judged that it would be unlikely that they would be picked up again - getting out under Cat and Mouse might lead to total release. They would be proved correct in the months to come.

Clink on images to enlarge