| HOME | TRIBUNAL HOME |

December 1916

In November’s look at the Tribunal we discovered the increasing presence of women in the pages of the newspaper. As 1916 wore to an end, the CO movement increasingly began to rely on the contributions of those who could not for one reason or another, be conscripted - those exempt on medical grounds, men over 41 but, for the most part, a group of politically active, passionate and campaigning women.

The three issues of the Tribunal issued in December would be dominated by pieces written by some of these women, and they are the focus of this month’s article.

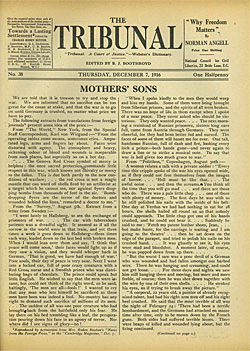

Mother’s Sons - 7th December 1916

Reprints of interesting articles from a variety of publications allowed the NCF to highlight articles that the readers of the Tribunal would find interesting and help them to spread a pacifist message. This article, “Mother’s Sons” was written by Dorothy Roden Buxton for the Cambridge Magazine, a periodical that was one of the only sources of news from around the world available to wartime Britain. It discusses the universality of suffering caused by war and promotes what would have been a radical viewpoint in 1916 - that all soldiers of all nations, Entente and Alliance, were united in the horror and brutality of war.

To today’s audiences it’s rare that anyone would think that German soldiers and British soldiers of the first world war were fundamentally different. But to an audience in 1916 bombarded with propaganda extolling the virtues of the british Tommy and the brutality of his German and Austro-Hungarian equivalents, even proposing that German soldiers might be human would have been a controversial topic.

world war were fundamentally different. But to an audience in 1916 bombarded with propaganda extolling the virtues of the british Tommy and the brutality of his German and Austro-Hungarian equivalents, even proposing that German soldiers might be human would have been a controversial topic.

Dorothy Roden Buxton uses letters from Sweden and Denmark to show that no matter the nation or cause, the grinding war was destroying the lives and humanity of young men all over Europe. The almost unbelievable descriptions of the “one single scream from thousands of despairing throats” as young German men left in no man’s land realised their deaths were nearing, and the madness of returning prisoners of war with “no hope of life in them” show that the war was killing all equally - every victim a “Mother’s Son”.

Dorothy’s compilations of “Notes from the Foreign Press” inspired international efforts to alleviate suffering and famine in the aftermath of the First World War, when Britain and France continued to push a food blockade on the starving men, women and children of Germany and Austria-Hungary. Over time, this “Fight the Famine Fund” would become one of the world’s best known charities - Save the Children.

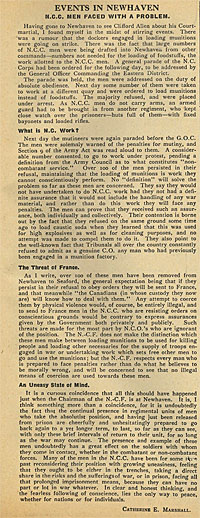

Events in Newhaven - 7th December 1916

Women also formed part of the Tribunal’s team of roving journalists, sending reports of CO activity from around the country. “Events in Newhaven” was written by Catherine Marshall a leading anti-conscriptionist and pre-war Suffragist, while she was in Newhaven after visiting Clifford Allen during his imprisonment there. Not only is this article important in showing how the Tribunal got it’s news, but also that it marks one of the increasingly rare appearances of the “forgotten” Conscientious Objectors - the men of the Non-Combatant Corps (NCC). The NCC were rarely covered in the Tribunal in 1916 as the rush of events overtook the NCF and focused their attention on the Absolutists.

The article covers an incident common in the lives of NCC men - refusing an order to work with war-related material. Newhaven saw the arrest of many NCC men who refused to move military material, arms and munitions. Large numbers of men refused this specific order and spent time under armed guard, confined to camp.

The article covers an incident common in the lives of NCC men - refusing an order to work with war-related material. Newhaven saw the arrest of many NCC men who refused to move military material, arms and munitions. Large numbers of men refused this specific order and spent time under armed guard, confined to camp.

Though similar to the Absolutist position in this specific instance, Marshall takes a rather high hand, distinguishing between the two types of CO - “the N.-C.F. does not make the distinction these men do” - and clearly outlines the primacy of the Absolutist position in both her eyes and those of the Tribunal by attributing the will of the NCC men to resist to the presence of “men who take the absolutist position”.

Marshall, though faithfully recording the events at Newhaven, may well be wrong in this case. While absolutists transitioning from civilian to criminal and from prison to prison may well have inspired the resistance of some NCC men, deciding to take up non-combatant Army Service was not a simple or a single decision. The Military Service records of NCC men are full of large and small acts of resistance - a refusal to compromise their principles by moving munitions, or weapons or even components that might have been made into weapons. The men who joined the NCC were Conscientious Objectors as much as any others and faced a complex balancing act in order to retain their objection to killing in war. As Catherine Marshall says “In clear and honest thinking, and the fearless following of Conscience, lies the only way to peace”. Alternativists and Absolutists both played their important role in paving this road.

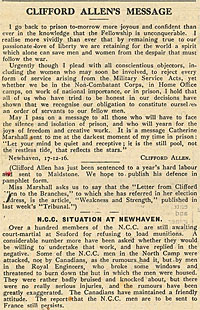

Clifford Allen’s Message - 21st December

Updates from Clifford Allen had been reported with a fairly high frequency despite the finality of his Farewell Letter to the NCF earlier in the year. This final message of 1916 forms the christmas message of the year, both in terms of a congratulation for the sterling work of both regional and national branches of the NCF and in terms of an encouragement about the year ahead.

December 1916 was full of fears around full-scale industrial conscription where every man and woman in Britain could be forcibly removed from their jobs and directed into war work. Allen exhorts to “all conscientious objectors, including the women that may soon be involved” to continue to resist the military machine and follow the example of those who have acknowledged an “obligation to constitute ourselves an order of servants to our fellow men”.

objectors, including the women that may soon be involved” to continue to resist the military machine and follow the example of those who have acknowledged an “obligation to constitute ourselves an order of servants to our fellow men”.

Unfortunately any message to NCF members at this time could not be optimistic and Allen is careful to write directly to those still to face the isolation and hunger of prison. Now facing a year’s hard labour and a potentially endless confinement, he shares a message from Catherine Marshall - “let your mind be quiet and receptive; it is the still pool, not the restless tide, that reflects the stars”

1917 would see an endlessly rising number of Conscientious Objectors forced into prison to put this advice to the test.