| HOME | TRIBUNAL HOME |

November 1916

November finds the Tribunal in a stable and popular pattern. Even though it’s original writers and editors were in prison, the office and printers were under constant threat of raids and government suppression and, at with that knowledge that at any moment the paper could be shut down permanently, the staff of the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF) managed to continue publishing as they had since March 1916, nine months earlier.

This month’s look at the Tribunal, then, will cover the news of November 1916 as well as taking the opportunity to get a little insight into the everyday details of the lives of those supporting COs up and down the country.

But first, the News.

The Australian Victory - 2nd November 1916

Hot on the heels of the Australian NCF’s telegram to the NCF in Britain must have come news of the Australian conscription referendum. Uniquely among the Commonwealth nations, Australia did not impose overseas conscription on it’s citizens, but instead put the concept of compelling obedience to the state to a vote - which was won by anti-conscription campaigners. With a 91,000 majority, the vote wasn’t enough to put the issue to sleep - another referendum would be hastily held that would return and even more astoundingly substantial majority.

Fenner’s article on this, the First Australian referendum doesn’t say all that much - we can gather that a telegram with the results had reached Britain by November, but with results only being called on the 29th, substantial news would have to wait. Nevertheless, the result would have been an outstanding vote of confidence for the NCF in Britain, which Fenner echoes:

telegram with the results had reached Britain by November, but with results only being called on the 29th, substantial news would have to wait. Nevertheless, the result would have been an outstanding vote of confidence for the NCF in Britain, which Fenner echoes:

“It is an inspiration to us, no less than it must be to them. Together we will go forward until the last vestige of Militarism has disappeared from the world. May our labours hasten that day!”

It would have seemed a victory for the anti-militarist cause, and with victories hard to come buy in 1916, the news would have been very welcome indeed.

News of Clifford Allen - 2nd November 1916

August’s issue contained the “Chairman’s Farewell”, Clifford Allen’s last words to the NCF as a free man. In the meantime, he had been arrested, tried as an absentee and delivered to the army. Soon after he was tried by Court Martial and sentenced to one year’s Hard Labour in Wormwood Scrubs. This article records the “First letter written by Clifford Allen since he entered Wormwood Scrubs”, and tells us as much about the prison system as it does about Allen’s experiences.

The fact that Allen’s first letter to the NCF comes so late after his sentencing on 18th of August is down to the practice of forbidding letter writing to and from prisoners until they had passed through the “solitary confinement stage”. While it might seem shocking now to force prisoners into two months of solitary confinement with no communication, the prison system wasn’t intended to reform or even punish Conscientious Objectors - it was supposed to break them.

Nevertheless, Allen emerges from solitary only to reject the Home Office Scheme, and to sound quite resolute in the process with a “mind as unalterable as ever against ‘civil work’”. The letter also gives us a look into how the Home Office Scheme was operating; granting hearings to COs to decide how “genuine” their convictions were before making the offer of out-of-prison work to a chosen few under heavy conditions. While many COs were judged as “genuine” those who were not, often political objectors, could only look forward to interminable prison sentences.

Though Allen was in prison, there’s still much of the Chairman of the NCF in his letter. Ever the master politician and conciliator, he asks to “be remembered to the N.-C.F. and the I.L.P, both to those who refuse and those who accept Alternative Service”. Mindful of the rift in the movement forestalled by his own actions in August, Allen continues to make his point heard - all objectors can be united in one organisation, the NCF.

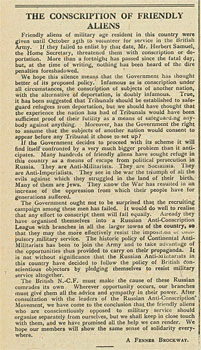

Conscription of Friendly Aliens - 9th November 1916

The introduction of the Military Service Act in 1916 was not the end of Conscription legislation in Britain during the war. Throughout 1916-1918, the act was continually extended, each time catching more and more men in it’s grasp, consistently adding to the total numbers of COs every time it was extended. This article shows the problems inherent in hastily extending the act to grab more men to throw into the charnel house of the Western Front.

“Friendly aliens” w ere men of military age from the nations on the same “side” as Britain during the war. While there were many thousands of men this applied to, from hundreds of different nations, the major group as far as the story of COs goes were Russians. As the Tribunal put it:

ere men of military age from the nations on the same “side” as Britain during the war. While there were many thousands of men this applied to, from hundreds of different nations, the major group as far as the story of COs goes were Russians. As the Tribunal put it:

“Many hundreds of of friendly aliens have sought refuge in this country as a means of escaping from political persecution in Russia. They are anti-militarists. They are socialists. they are anti-imperialists. They see in war the triumph of all the evils against which they struggled in the land of their birth. Many of them are Jews. They know the war has resulted in an increase of the oppression from which their people have for generations suffered”

If you’ve been keeping up with the Tribunal, or are familiar with the story of CO’s, you’ll no doubt be able to foresee how successful trying to conscript these men would be. The Tribunal certainly could:

“The Government ought not to be surprised that the recruitment campaign among these men has failed. It would do well to realise that any effort to conscript them will fail equally”.

Anarchists, Communists, Socialists and strictly observant religious Jews? The Tribunal was right. The push to conscript Russian refugees and immigrants would fail, and hundreds in London alone would soon be in prison as Conscientious Objectors.

Adverts and Asides - November

One of the few types of articles we haven’t looked at in The Tribunal is the small section on the back page of each issue - usually reserved for adverts, asides and statistics. Four out of Five of November’s issues feature this section, and it’s surprisingly useful to the study of COs! Aside from occasionally giving names and addresses of men otherwise difficult to track down, the back page usually features something to and from the unspoken heroes of the NCF - the wives, sisters, mothers and friends who carried the CO movement from mid-1916 to 1919.

The Tribunal was edited, published and in many cases almost entirely written by women. Maude Royden, featured in last month’s look at the paper, was a frequent contributor, but most of the articles written and added in the Tribunal aren’t long enough to warrant an author byline, so it can be difficult to identify which articles the many female authors produced.

However, one at least in November was definitely written by a woman;

“The following extract from the letter from the wife of a CO is interesting from more than one point of view:

“I have official news from wormwood scrubs that my husband... had accepted work under civil control... I would rather that he had gone through with the out and out resisting, but alas I have no say in the matter. It is very strange that men of the opinions I have known have gone to prison and in a few weeks taken the first opportunity of release. I am convinced now that women have protected men too much from the domestic side of life. Women are often shut up in houses week in week out and men have thought nothing about it...”

I’ve included this article as it shows a couple of different things. First, that Objection wasn’t a decision limited to the objector himself, but one that was usually made after discussion with people around them. In this case, the unknown CO is accepting the Home Office Scheme and seems to be much less committed to the Absolutist position than his wife!

the objector himself, but one that was usually made after discussion with people around them. In this case, the unknown CO is accepting the Home Office Scheme and seems to be much less committed to the Absolutist position than his wife!

Aside from that, It’s an interesting piece because of what it says about the Tribunal and it’s staff. The many women who worked at the NCF headquarters on producing, printing and distributing the Tribunal weren’t just pacifists, but also committed suffragists, socialists and communists. In other words, they were feminists. There’s a great deal of irony in this piece at the sudden sight of men being forced into social roles (prison and the army) and finding themselves in an analogous position with women at home - “Two Kinds of Prison” indeed.

The adverts in the Tribunal are usually for helpers and companions - though sometimes for NCF jumble sales, which I think is a charming way to raise money for a dubiously legal subversive organisation - which can also shed some light on the experiences of women in the CO movement. They’re usually adverts for companions, most often coming from prominent members of the peace movement like Emily Hobhouse and Lila Brockway. Others come from mothers, wives and sisters of COs who are looking for additional help and support in their lives in the absence of husbands, sons and brothers. Either way they help to tell the story of an interconnected movement, hiring, supporting and working for each other independently.

We’re told much about women in the First World War getting new jobs and finding new opportunities where they could make munitions and get killed in factory explosions when corners were cut in a frantic effort to make ever more weapons of mass destruction, but Women in the CO movement were finding their voices more and more valuable as large sections of the NCF were carted off to prison. December, and the first months of 1917 would see these voices come to the fore.