| HOME | TRIBUNAL HOME |

July 1916

We left June’s Tribunal on the note that the civil government was about to unveil a new way of dealing with the “problem” of Conscientious Objectors in civilian and military detention.

The difficulties in dealing with Conscientious Objectors in military detention over the early months of 1916 had amassed until they reached a critical point when 34 COs were sentenced to Death. Military detention was not working, and civil imprisonment was already causing more problems that it was worth. The alternative became known as the “Home Office Scheme”, designed to remove COs from both civil and military detention and put them to relatively useful work around the country. Details of the Home Office Scheme can be found on our “Story of Conscientious Objection”. Much of the four issues of the newspaper in July would be concerned with some of the moral and ethical problems faced by COs with the advent of the new plan.

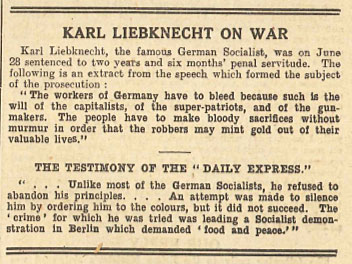

6th July 1916 KARL LIEBKNECHT ON WAR

Before looking at the formation and impact of the Home Office Scheme, the July 6th issue mentions a note on Karl Liebknecht, a German anti-war campaigner who would become an irregular feature in the pages of the Tribunal. Karl was imprisoned in June 1916 and would remain in various decrees of confinement until close to the end of the war. The featured extract of his speech could have been said by any socialist anti-war campaigner in any of the countries fighting:“the people have to make bloody sacrifices without murmur in order that the robbers may mint gold out of their valuable lives.”

Before looking at the formation and impact of the Home Office Scheme, the July 6th issue mentions a note on Karl Liebknecht, a German anti-war campaigner who would become an irregular feature in the pages of the Tribunal. Karl was imprisoned in June 1916 and would remain in various decrees of confinement until close to the end of the war. The featured extract of his speech could have been said by any socialist anti-war campaigner in any of the countries fighting:“the people have to make bloody sacrifices without murmur in order that the robbers may mint gold out of their valuable lives.”

The note finishes with an extract from the Daily Express condemning the treatment of Liebknecht by the German authorities

“The ‘crime’ for which he was tried was leading a Socialist demonstration in Berlin which demanded “food and peace””

The Daily Express was a vehement campaigner against British Socialists trying to carry out similar demonstrations at home. The Tribunal, as always, keenly aware of the hypocrisy of the wartime press.

6th July 1916 GOVERNMENT’S NEW SCHEME

The Home Office Scheme (HoS) proved controvertial in the CO community. This article served as the first introduction many readers of the Tribunal would have to the workings of the scheme, the first comment on it and the official NCF response. While the outcomes of the Home Office Scheme will appear in later months of the Tribunal, this article sums up some of it’s key points:

The Home Office Scheme (HoS) proved controvertial in the CO community. This article served as the first introduction many readers of the Tribunal would have to the workings of the scheme, the first comment on it and the official NCF response. While the outcomes of the Home Office Scheme will appear in later months of the Tribunal, this article sums up some of it’s key points:

Men tried for military crimes caused by their conscientious objection to military service will be assessed as COs, not as “soldiers”

“Genuine” COs may be released from civil prison to do work of national importance under government control

Released men would still be in the army - transferred to Reserve Class W - though not under military law

All men on the Home Office Scheme would have to sign forms acknowledging their responsibilities and rights as Army Reserve class W workers.

The news divided the Conscientious Objector movement. For thousands of men who had been given no exemption by their tribunal hearing, or had been given exemption from combatant service only, there suddenly appeared to be a new way of operating within the system. COs already in civil prisons for a military offence could leave prison in order to work on the scheme. Most significantly of all, disobeying military orders through an already established conscientious objection to military service was no longer ruled a military crime, but a civil one that could be dealt with under the HoS. This ensured that the terrible events of May and June could not be repeated.

Perhaps more significant from the Tribunal editors point of view than the announcement of the scheme was the reply to it. The most important issue they highlight is undoubtably point seven:

“men who are released from civil prisons to perform work of national importance will be transferred to Section W of the Army Reserve. They are thus retained as part of the Army... However formal the transfer to the Army Reserve may be, the effect is to perpetuate that military control to which the man objects”

This was the key moral issue for Conscientious Objectors - how could anyone choose to go on the scheme while maintaining that they were not a soldier? Transfer to the Army Reserve under the HoS meant no uniform, military law or obeying orders. But it did mean acknowledging that you were in the Army system - effectively agreeing to be a soldier! What did this mean for absolutists, men who refused to undertake any service as part of the war effort? Would they remain in prison, or be sent back to the army?

At this point, these questions and many others, could not be answered.

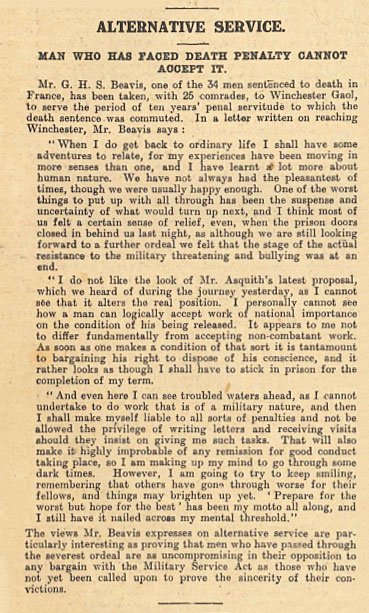

13th July 1916 Alternative Service

Man who has faced death penalty cannot accept it

This issue of the Tribunal features an extract from a letter written by Stuart Beavis, one of the 34 sentenced to death in France. In it, he outlines some of the key reasons why he would not take up the HoS:

This issue of the Tribunal features an extract from a letter written by Stuart Beavis, one of the 34 sentenced to death in France. In it, he outlines some of the key reasons why he would not take up the HoS:

“I personally cannot see how a man can logically accept work of national importance on the condition of his being released. It appears to me not to differ fundamentally from accepting non-combatant work. As soon as one makes a condition of that sort it is tantamount to bargaining his right to dispose of his conscience”

“And even here I can see troubled waters ahead as I cannot undertake to do work that is of a military nature”

The inclusion of a letter from Stuart Beavis is both an interesting and extremely clever piece of propaganda work for the Tribunal. The previous issue, as discussed above, had put forward the official NCF view of the Home Office Scheme - a firm refusal of it’s conditions. This was by no means the unanimous view of NCF members, and the central committee knew it. Including a letter from one of the men sentenced to death was a powerful statement that, even after such a terrible experience, this man would not compromise by accepting the scheme - so why would you?

The Tribunal even makes this point extremely explicit with the closing lines of the article:

“The views Mr Beavis expresses on alternative service are particularly interesting as proving that men who have passed through the severest ordeal are as uncompromising in their opposition to any bargain with the Military Service Act as those who have not yet been called upon to prove the sincerity of their conviction”

This article was chosen to highlight as it shows a new, and far more effective, type of NCF propaganda at work in the Tribunal. One of the wonderful things about the NCF, who were producing a newspaper that was effectively a prosecutable offence to read, is their absolute dedication to the highest, noblest propaganda. NCF leaflets are filled with high-minded appeals to solidarity, faith and wisdom. They always appeal to everyone as rational and calm. In a time of shock adverts, fictional stories about German atrocities and scurrilous rumours, this approach would nearly always fail.

It’s absolutely fascinating to see this piece - a subtle bit of emotional manipulation, and an appeal to a “noble sacrifice” not unlike recruitment propaganda, appearing in the Tribunal. Why did the editorial staff include this letter? Perhaps because for the first time, The NCF leadership seemed out of touch with members. Thousands of men were eager to take up the HoS and the local branches were reporting more and more support for the idea. The official stance was at odds to a popular alternative - and the whole movement seemed about to split in half. Propaganda was very necessary.

Conclusion

Most of the July issues of the Tribunal are concerned with the regular updates on the Houses of Parliament, COs in prison and Court Martial sentences. They provide absolutely invaluable information for anyone researching conscientious objectors, but add little to our understanding of the overall story.

July sees a community still getting over the shock of the death sentences revealed in June. Reading through the issues, it feels as if before anyone could really get to grips with the events of June, July and the proposals of the Home Office Scheme were upon them. While the National Committee of the NCF quickly formed an official response, there was a great deal of uncertainty about what the Home Office Scheme would mean for individual COs and for the wider movement. With the imprisonment of most of the leaders of the NCF, it looked as if a crisis was building. Only quick action in August would stave it off and keep the CO movement going forward.