| HOME | TRIBUNAL HOME |

July 1918

By July 1918, Conscription had been extended to the limit, harassment of the NCF had died down to a constant background hum, and the war ground on for another month. Though from our vantage point the deadlock was soon to break on the western front, bringing an end to the war, to the writers of the Tribunal it was another month of the struggle. Issues of the Tribunal in July are filled with reprints and updates, painting a picture of an organisation (if not the whole country) ground down by the endless war.

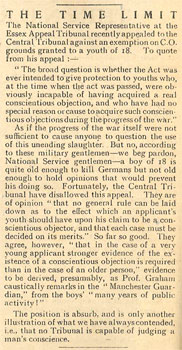

4th July: The Time Limit

Though the extension of the Military Service Act had featured prominently in the pages of the Tribunal in May and June, most of the attention had focused on the older age bracket, but the new version of the act also conscripted younger men - sending thousands of 17-18 year old to Tribunals. Here, they were posed with an additional problem, as this article relates:

“The broad question is whether the Act was ever intended to give protection to youths who at the time the act was passed, were obviously incapable of having acquired a conscientious objection, and who have had no special reason or cause to acquire such conscientious objections during the progress of the war”

“The broad question is whether the Act was ever intended to give protection to youths who at the time the act was passed, were obviously incapable of having acquired a conscientious objection, and who have had no special reason or cause to acquire such conscientious objections during the progress of the war”

The 1916 act had stipulated that a CO must have had an objection to war before 1914 - in the hope of “weeding out” anyone who had developed one in response to the war. Though this in itself is ludicrous - an objection to war developing from your first encounter with the reality of it is as legitimate as any other - the new intake of boys would have been 13 and 14 when the war began. Judged as too young to have formed a conscientious objection before the war, any that had developed since was, in the eyes of Tribunals around the country, apriori invalid.

Though the article notes that the Central Tribunal had ruled that “no general rule can be laid down as to the effect which an applicants youth should have on his claim to be a conscientious objector”, they had also ruled that “stronger evidence of a conscientious objection is required than in the case of an older person”.

Absurdity aside - as the Tribunal wryly notes, perhaps a boy would have had “many years of public activity!” behind his objection - this ruling reveals much about the operation of the Military Service Act in 1918. Older men were wanted for labour battalions, work at home and behind the lines. 18 year olds were fresh fodder for the ongoing battles at the front. Making exemption harder to obtain for younger men was a calculated tactic to force them into the fight.

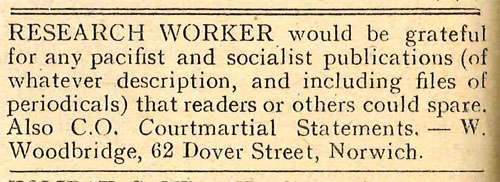

4th July: Research worker

It’s been a few months since we looked at the classified advertisements in the Tribunal, but one from the 4th of July issue caught my eye. After two years of Conscription and Conscientious Objection, a researcher is trying to collate the first archive of material. Asking for “pacifist and socialist publications” and “C.O Court-martial statements”, they’re looking for exactly the material that we are, 100 years later.

Seeing the ad, I can’t help but wonder at the response. Was it easy to encourage COs to give up their court martial statements, or even a copy of them? Did a deluge of forms and papers, notes, biographies and letters pour in, and what happened to them if they did? Did they form the beginning of one of the large collections in Hull, Leeds, Friends House, the WCML, or our own archive? Or is there a hoard of CO material out there still to be found?

Whatever the result of the ad, the indications of early research show something important about the conception of the CO movement. It wasn’t just a temporary situation, but was beginning to be seen as a foundation for future work - the beginnings of a wider anti-war movement and simply the first expression of a struggle to come. The experiences and lessons of COs needed to be collected, codified and understood - and used to further the cause in the future.

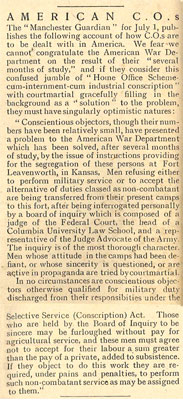

11th July: American COs

June had featured early rumblings of Conscription in the USA and the organisations gathering to oppose it. News of American COs travelled rather quicker than news of conscription in New Zealand, or anti-conscriptionists in Australia, and American COs were to feature frequently in the Tribunal in 1918. Of course, as the Tribunal had seen around the world, no-one had a good solution for the “CO Problem”, preferring punishment, confusion and arbitrary detention:

“Men refusing either to perform military duties of to accept the alternative duties classed as non-combatant are being transferred from their present camps to this ford [Leavenworth, Kansas]... Men whose attitude in the camps has been defiant, or whose sincerity is questioned, or are active in propaganda are tried by court martial.”

COs were to be confined and assessed, in a similar way to the operation of the Central Tribunal in Britain. From there, they were to be sent to agricultural work (the Home Office scheme analogue), or, most sinisterly:

“If they object to do this work they are required, under pains and penalties, to perform such non-combatant service as may be assigned to them.”

There was to be no provision for civilian prison in the US - work camps or the army threatened for hundreds of men.

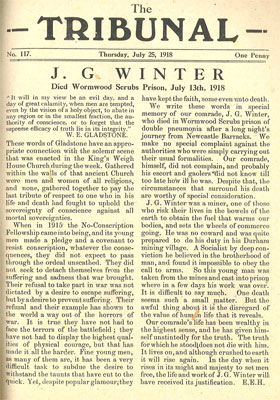

25th July: J.G Winter

Keeping up it’s sad tradition, the Tribunal committed itself to printing the obituaries of COs that died in prisons and work camps around the country. The death of John Winter was no exception. John, a miner, had been “combed out” in the latest round of the Tribunal’s endless quest to grab more men. As a “socialist by deep conviction” who believed “in the brotherhood of man, and  found it impossible to obey the call to arms”, he refused call up, was faced court martial inNewcastle Barracks and was swiftly sent to Wormwood Scrubs - all a very usual procedure. Almost immediately upon arriving at the prison, he died of double pneumonia.

found it impossible to obey the call to arms”, he refused call up, was faced court martial inNewcastle Barracks and was swiftly sent to Wormwood Scrubs - all a very usual procedure. Almost immediately upon arriving at the prison, he died of double pneumonia.

The Tribunal was shocked by his rapid death, even though “One death seems such a small matter”, as the “awful thing about it is the disregard of the value of human life that it reveals.” It seemed to the writer of the article that John had been stoic through long-term suffering “our comrade, himself, did not complain”, and that there was “no special complaint against the authorities”.

Months later, John Winter’s death would be more easily explained. A short infection period, rapid decline and death by double pneumonia points at only one culprit - the Spanish Flu. Winter was most likely the first CO to die in the pandemic - but certainly not the last.

Clink on images to enlarge