| HOME | TRIBUNAL HOME |

May 1918

The Tribunal of May 1918 looked very different from it’s original incarnation - and even from the final issue of April. The 22nd of April raid on the NCF offices and printworks had achieved it’s goal after two years - the end of the Tribunal as was, but failed to silence the newspaper entirely. From the 2nd of May onwards, the Tribunal would appear in reduced, but still defiant form. Despite raids and rationing, arrest and shortages, while using portable, hand-powered printing machines and moving from location to location under cover, the Tribunal stayed in press for another two years.

May 1918 focused on the effects of the fifth extension to the Military Service Act, passed originally in April, but almost lost in the scrabble to evade and bypass the effects of military and civil censorship. The May Act extended the age range of conscripts up and downwards, extending from 18-41 to 17-51, and bringing in a new group of men (and boys) to active involvement in the CO movement. it had been passed and implemented in a panic. The German spring offensive had, by May, petered to a halt, but not before causing a manpower crisis in the British and French armies. For a few weeks, the balance of the war had turned against the Entente - and a desperate attempt to shore up the line with whatever men the army could scrounge again looked to forcible conscription as a means to prolong the war.

2nd May: The New man power act

The “New man power act” article outlines the expansion of the Military Service act, its effects on newly called up men, and on those who had already been exempted by a tribunal.

Extending the act to a new age category was not overly complicated. Men between 41 and 51 had been totally exempted from call up prior to 1918, but issuing them with call-up papers and the opportunity to apply to a Tribunal was not difficult, the act simply creating two new groups of men eligible for conscription - first men between 41 and 44, and second the 44-51 age group. The Tribunal issued the same instructions to potential COs outlining the grounds upon which they could be exempt, the system of applying to Tribunals and the rules surrounding Medical Examinations as had been available to men between 18 and 41 since 1916. Aside from creating another group of COs, little had changed.

Men who had already gained exemption were the second major group targeted by the May act. The “combing out” process which had begun in 1917, went into it’s final phase, as the country was scoured for the last remaining men fit for combatant duties. All certificates of exemption, starting with those issued to 18-23 year old men, would be revised - with an eye towards forcing them into the army. COs who had been granted absolute exemption (all ~90 of them), and men exempted on medical grounds would be ignored - but all others faced another Tribunal hearing, one now even more determined to ignore any domestic, or economic impediments to feeding another soldier into the charnel house of the front.

This proved tricky for many COs. Where Tribunals had refused to listen to a Conscientious Objection when submitted alongside another - especially exemption on the grounds of a Nationally Important occupation or Domestic situation. The Tribunal noted with concern that both groups of men would see their exemptions lost under the far more severe exemption clauses of the new act. They urged readers to make their Conscientious Objection known as soon as possible, and not to rely on the exemptions they had gained in 1916 and 1917, which were soon to be made invalid.

9th May: A Call to Action

The new act created new COs, and the Tribunal was ready with a call to action directed squarely at them. The men caught up in the new act would not have been ignorant of the COs conscripted in 1916-1918, and many had been involved in the activities of the NCF, Society of Friends and Fellowship of Reconciliation. Still others were fathers, brothers or uncles of COs, political allies, employers and colleagues, comrades and fellow travellers. Many had been following the struggles of the younger men who went before them. Dr Alfred Salter, socialist, republican, free health service pioneer and all-round hero, spoke at the London NCF convention, as one of these men:

“the moment has now come to us... as it came previously to men between 18 and 41, to decide whether or not we shall obey the State or obey our deepest and most profound convictions. It is a dilemma into which we should never have been forced, but it is not a dilemma of our own seeking; it is a dilemma that we have to face, and we have to face it humbly, courageously and determinedly, as the men before us have done.... The younger men have done their part; it is for us older men to shew ourselves worthy comrades of those gone before”

Other conferences and conventions around the country proclaimed the same message. No easy capitulation to conscription would come from the new group of men. Around the country, they waited patiently for call-up, and the chance to prove their conscientious principles, to achieve the “long delayed victory... the downfall of conscription and militarism itself, and the liberation of the multitudes of it’s captives, for whose sake and whose children’s sake we take our stand.”

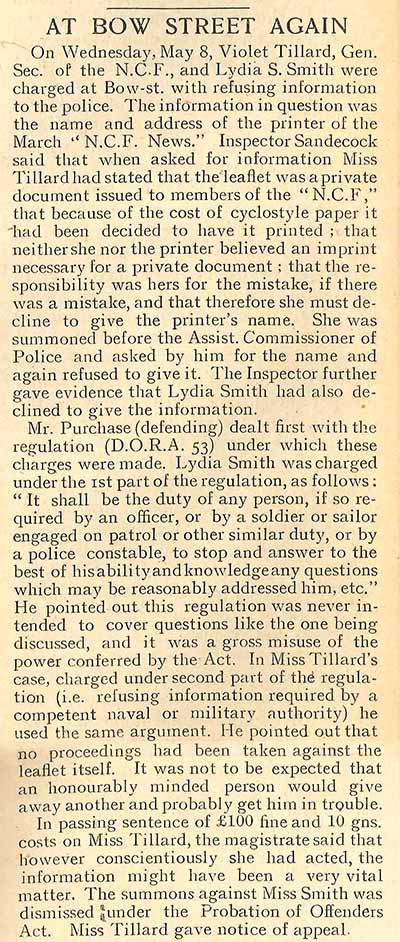

16th May: At Bow Street Again

May saw continued harassment of the NCF, both in the court room and on the street. Joan Beauchamp and Bertrand Russell had their appeals dismissed and both would soon see the inside of prison, Russell for six months and Beauchamp for one.

Having imprisoned the publisher and main contributor of the Tribunal, the Police continued a low grade harassment operation, bringing in key editorial staff, Violet Tillard and Lydia Smith, for the terrible crime of “not answering questions”. Refusing to give up information to the police that would have led them to the remaining print works producing NCF material, Smith and Tillard were prosecuted under DORA, fined, and released. It would not be the last time they would be arrested.

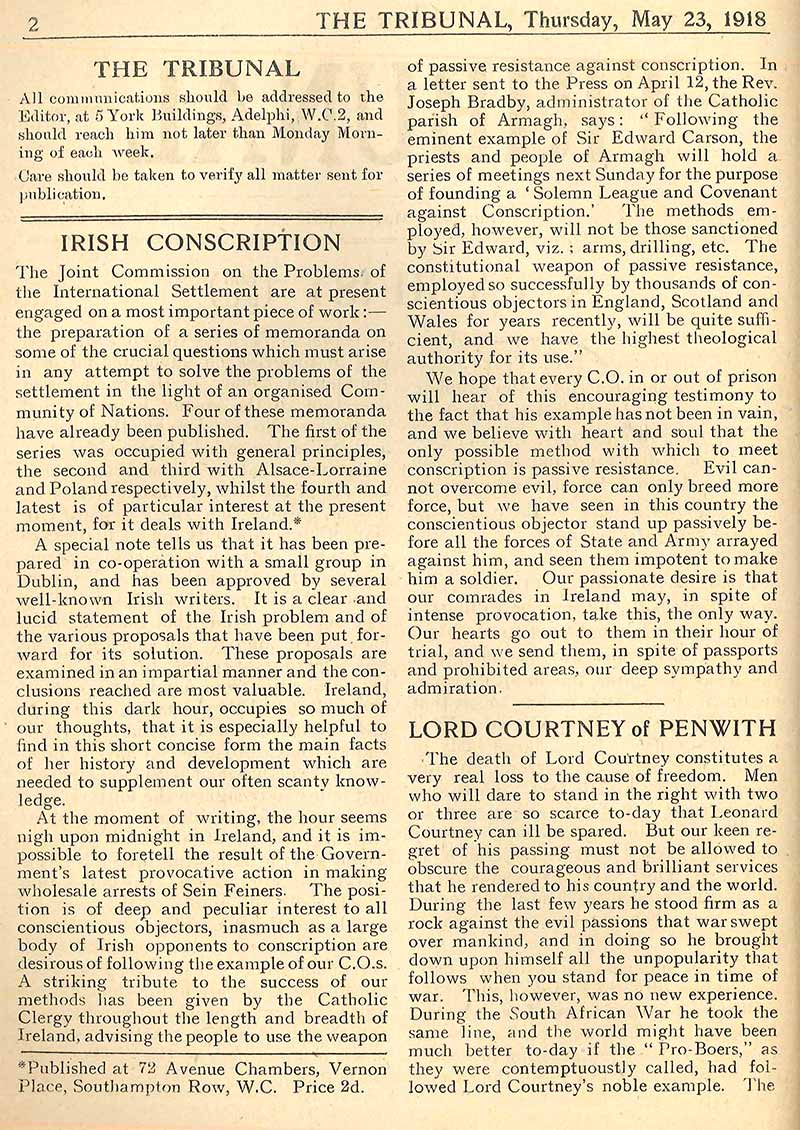

May 23rd: Irish Conscription

The 1918 Military Service Act did not simply conscript older men into the army. It also extended conscription to areas it had not been previously applied. The Channel Islands and the Isle of Man were included, but most importantly, Conscription was introduced in Ireland for the first time.

It did not result in a tide of new conscripts, reluctant but accepting of their fate as soldiers, but civil unrest, disobedience and war. The Act had been passed in opposition to the vote of every Irish Nationalist MP. Ostensibly passed as part of a bargain for Home Rule, the extension of the act infuriated Irish politicians and nationalists, creating a crisis that would feed into the growing turmoil in Ireland - and contribute to the Civil War that was about to erupt.

From May 1918, the Tribunal reports only on increasing resistance to the imposition of Conscription in Ireland, but with a heavy dose of foreboding. While the article states that the “Catholic clergy throughout the length and breadth of Ireland” have been “advising the people to use the weapon of passive resistance against conscription”, but that with the arrest of 150 Sinn Fein politicians and supporters - key opponents of Conscription - in April, “the hour seems night upon midnight in Ireland”.

From May 1918, the Tribunal reports only on increasing resistance to the imposition of Conscription in Ireland, but with a heavy dose of foreboding. While the article states that the “Catholic clergy throughout the length and breadth of Ireland” have been “advising the people to use the weapon of passive resistance against conscription”, but that with the arrest of 150 Sinn Fein politicians and supporters - key opponents of Conscription - in April, “the hour seems night upon midnight in Ireland”.

The article is notable not for the information it presents, but for the conclusion it comes to. The situation in Ireland was rapidly deteriorating. Spurious arrests, Conscription and the British Cabinet’s resolution to take a hard line on the “Irish Question” threatened what the Tribunal saw as the beginnings of a pacifist movement to resist conscription - one that they hoped to see:

“Evil cannot overcome evil, force can only breed more force, but we have seen in in this country the conscientious objector stand up passively before all the forces of State and Army arrayed against him, and seen them impotent to make him a soldier. Our passionate desire is that our comrades in Ireland may, in spite of intense provocation, take this, the only way. Our hearts go out to them in their hour of trial, and we send them, in spite of passports and prohibited areas, our deep sympathy and admiration.”

Conscription never came into force in Ireland, due in part to the determined resistance of all those who stood up against it in April and May 1918. The Tribunal would return to cover the events in Ireland in more detail - and chart the descent into war that the Military Service Act made ever more likely.

that had settled over the war since 1914, March proved to be a nervous and cautious month inng tion, non-violent resistance. In keeping with this month’s cautious and careful Tribunal, it does not call for action, so much as it encourages persistence and the value of setting an example.

Clink on images to enlarge