|

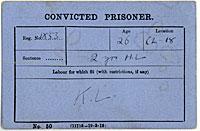

Card from prison door which identified the resident prisoner. :: >

'HL' stands for hard labour.

One of a series of postcards :: >

Prison rules on back of letter sent to new prisoners. ::>

|

Prisons are not pleasant places today but they were even grimmer at the beginning of the 20th century.

Many conscientious objectors were imprisoned for their refusal to accept call-up and often sentenced to ‘hard labour’ (compulsory manual work). The 1916 conscription law meant that every eligible man, CO or not, was now a soldier. So COs faced court martial and imprisonment in military jails, where life was very tough indeed.

|

But most COs ended up sooner or later in civilian prisons. Some were harsh and brutal places, others had a reputation for treating prisoners reasonably well. But all the prisons operated by the same rules.

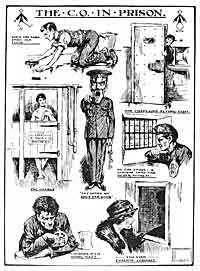

One of these was ‘the silence rule’, hard to imagine today. By this rule, prisoners were not allowed to speak – at all. Even the warders were not allowed to speak to prisoners, except to give them orders or reprimands. The more humane prison officers also had to be careful: as one CO prisoner explained, ‘The warders had to maintain a hostile front, lest they should be accused of being too friendly.’

Every prisoner was alone in a cell. The cells were small, with just one window – high up in the wall so that the prisoner had to stand on a stool to see out. Needless to say, anyone caught (through the spyhole in the cell door) looking out of his window was punished.

|

|

|

|

One of a series of postcards

|

The cells were very uncomfortable. For the first month a prisoner slept on bare boards. A mattress, pillow and blanket were issued later. For the first month the prisoner did not leave his cell except for about half an hour in the exercise yard. The days were spent working (such as sewing mailbags, or making rope and baskets).

After the first month, prisoners worked daily ‘ in association’ – together in big workshops or assembly halls – and still in silence. In fact the COs did occasionally manage to have quick whispered conversations. They also learned Morse code (or invented their own codes) to tap signals along the water pipes that ran through every cell.

Most of the men were given a Bible and maybe a prayer book. They could also read a book (exchanged for another every 2 weeks) from the prison library, but the prison library was not well-stocked. Later, prisoners’ relatives and friends were able to donate books, which improved things.

In the cells the men had only a slate to write on, so nothing they wrote could be kept or passed on. Once a month (starting after the first month in prison) they were given paper and pens to write censored letters home. Some of the men learned how to hide supplies of ink and make pens with sewing needles, and with these could write small on sheets of toilet paper. Some even created their own prison newsletter this way, smuggled from man to man for everyone to read.

After the first month, prisoners were allowed to have visitors, but were separated from them by iron bars or cubicles with a wire grille. A warder was always present, to ensure that the talk was only about domestic and family matters. In January 1918 the Home Office announced some relaxation of rules for COs who had served more than twelve months in prison. For these men, visits now took place in an ordinary room (though still with a repressive warder present). They now also had two exercise periods a day – in which, at last, conversation was allowed.

Prison diet was unappealing: porridge and bread for breakfast and evening meal, and bread, potatoes and a little meat in the middle of the day, perhaps enlivened with a bit of suet pudding. Vegetarians had to leave the meat, so they were later allowed a piece of cheese instead, or an extra vegetable. (It was not long before many of the prisoners began asking for a vegetarian diet.) Food was also used as a punishment: bread and water only. The other main punishment was solitary confinement.

Following their release from prison in 1919, many COs began working hard to expose the appalling conditions in prisons. They talked and wrote about their experiences and worked through the Penal Reform League. As a result, a Prison System Inquiry Committee was set up. The Committee’s two secretaries were Stephen Hobhouse and Fenner Brockway, both of them COs who had been imprisoned.

Public pressure for changes to the prison system was given added force by a Report published in 1922. This described imprisonment as demoralising and dehumanising. There were immediate results. Prisoners no longer had their hair forcibly close-cropped, and they no longer had to wear the traditional outfits patterned with arrows. They were now able to shave themselves (previously even safety razors were banned). The silence rule was applied much less stringently. Greater opportunities for education were provided, so prisoners could use their cell-time for learning. ‘Hard labour’ was made more sensible and useful, and an official 7-hour working day was introduced.

|