|

WOMEN WORKING FOR PEACE |

||

THE MEN WHO SAID NO | ROAD TO CONSCRIPTION | CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTION | PRISONS | SENTENCED TO DEATH | TRIBUNALS | WIDER CONTEXT | INDEX |

||

|

||

| THE HAGUE CONFERENCE 1915 | ||

|

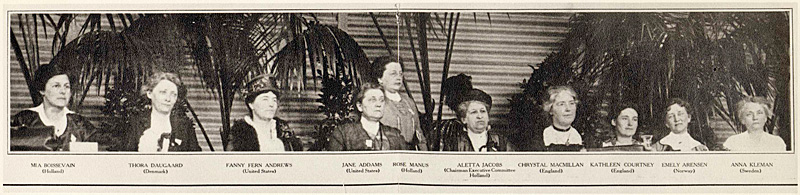

In April 1915, about 1200 women from the warring countries gathered together in The Hague, for the Women’s International Congress. The overwhelming majority were from Holland, as others had great difficulties getting there. They came from Austria, Belgium, Britain, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and the United States. French and Russian women were not allowed to attend. 180 British women had applied to come but the government refused at first to allow passports, eventually agreeing to issue 24 to women chosen by the Home Secretary. But the Admiralty then closed the North Sea to shipping! The only British women able to attend were Chrystal Macmillan and Kathleen Courtney who had already travelled to the Hague to help organise it, and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence who came from the States. Those travelling from the States risked their lives sailing across the Atlantic in a ship that was unable to fly the American flag and could have been torpedoed. Five Belgian delegates arrived to great applause having surprisingly secured permits from the occupying German authorities. Messages of support came from as far away as India, Brazil and South Africa. The British press treated this with the usual contempt – the Evening Standard said ‘Women peace fanatics are becoming a nuisance and a bore’, their efforts were dismissed as amateurish, they were mocked by the Daily Express as ‘peacettes’ and generally the press was disappointed the women did not come to blows. To hold the conference at all during the war was an amazing feat of organisation, and bravery. It was the first international meeting to draw up an outline of the principles needed for a peace settlement to succeed. The Covenant of the League of Nations after the war is remarkably similar to the 20 resolutions passed by the delegates. They included democratic control of foreign policy, with no secret treaties, universal disarmament, future international disputes to be referred to arbitration – and of course, equal political rights for women, and the involvement of ordinary men and women in the final peace conference. The delegates held a minute’s silence for all those killed in the war so far – Rosika Schwimmer described the mood: ‘we had one who learned that her son had been killed – and women who had learned two days earlier that their husbands had been killed, and women who had come from belligerent countries full of the unspeakable horror, of the physical horror of war, these women sat there with their anguish and sorrows, quiet, superb, poised, and with only one thought, ‘What can we do to save the others from similar sorrow?’ It was her idea that the resolutions passed by the Congress should be taken in person to the heads of the belligerent and neutral governments and to the President of the United States. Many thought the idea impractical and impossible, but she persuaded them with her eloquence. Between May and August 1915 thirteen of the women, in two groups, visited top statesmen in fourteen capitals: Berlin, Berne, Budapest, Christiana (now Oslo), Copenhagen, The Hague, Le Havre (seat of the deposed Belgian government), London, Paris, Petrograd (now St. Petersburg), Rome, Stockholm, Vienna and Washington. Women from the fighting countries were chosen to visit the neutral governments, and vice versa. Chrystal Macmillan from Britain was one of them. They wanted the neutral countries to set up a mediating conference. They succeeded in meeting top level statesmen – for example in Britain Catherine Marshall arranged meetings with the Foreign Secretary and the Prime Minister. Everywhere they found all the governments had convinced themselves they were fighting ‘in self-defence’ and were waiting for the neutral countries to intervene. In Austria, Jane Addams (American chair of the Congress) said to the Prime Minister that ‘It perhaps seems to you very foolish that women should go about in this way; but after all, the world itself is so strange in this war situation that our mission may be no more strange or foolish than the rest.’ He replied ‘Foolish? These are the first sensible words that been uttered in this room for ten months.’ As history shows, the women did not succeed. Every government seemed to be waiting for some other government to take the first step to peace.

|

|

|