For members of the Church of England opposing the First World War, whether generally or specifically as conscientious objectors to military service, an immediate stumbling-block was the final paragraph of Article 37 of the Thirty Nine Articles of Religion confirmed and subscribed by the Archbishop, Bishops and Clergy of the Convocation of Canterbury in 1571 and since 1662 published in the Church of England Book of Common Prayer, as contributing to the doctrinal basis of the Anglican Church. The paragraph states:

“It is lawful for Christian men at the commandment of the Magistrate to wear weapons and serve in the wars.”

Essentially, it derives from the “Just War” principle, as developed in Christian theology by Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century, whereby war was justifiable if conducted by a lawful authority (“at the commandment of the Magistrate”), for a just cause and by fair means (e.g. minimal harm to non-combatants).

It may reasonably be commented that both the development of the Just War doctrine and its inclusion in the Thirty Nine Articles were overt admissions that war always and necessarily falls short of the Christian ideal exemplified in the Sermon on the Mount (Authorised Version): “blessed are the peacemakers”; love your enemies”; “whosever shall smite thee on the right cheek, turn to him the other also” - all expressly presented as a fuller interpretation of the Sixth of the Ten Commandments handed down to Moses, “Thou shalt not kill”.

In the early 20th century there were a number of Anglican churches where the Ten Commandments were prominently displayed, commonly in two columns, one either side of the chancel arch. Thus, “Thou shalt not kill” would be prominent at the top of the right-hand column, far more visible than the small print of the last sentence of the 37th Article tucked away in the Prayer Book.

Moreover, the 37th Article’s derogation from the Sixth Commandment was permissive, not obligatory. Declaring it lawful for a Christian man to wear weapons did not mean that he had an inalienable duty to do so, a distinction recognised by Parliament in the Military Service Act, even though exercise of that distinction by the Military Service Tribunals was widely and woefully deficient.

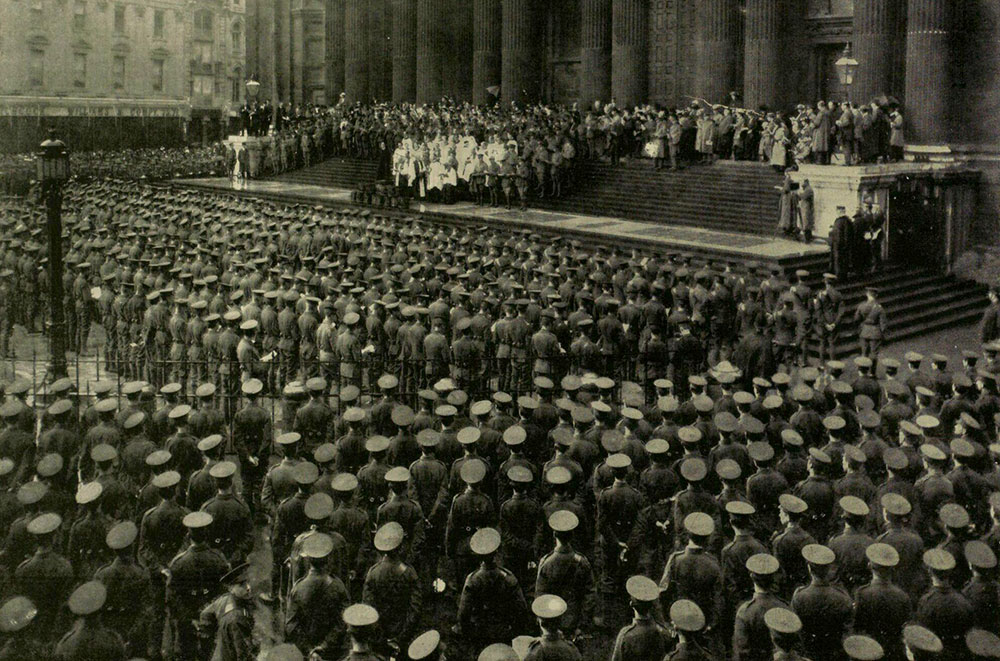

So far as the practice of the Church of England was concerned, one bishop was not satisfied even with the compromise between the Christian ideal and state realpolitik of the Just War. Arthur Winnington-Ingram, Bishop of London, threw himself into supporting the war as a great crusade; Herbert Asquith, Prime Minister, described his pitch as "jingoism of the shallowest kind," as the bishop spoke in recruiting drives and urged younger clergy to consider enlisting as soldiers. He dismissed conscientious objection as founded on an entire misunderstanding of the Bible. William Gascoyne-Cecil, who became Bishop of Exeter in 1917, was marginally more tolerant, accepting religious objection, but after visiting Princetown Work Centre, within his diocese, suggested that non-religious objectors should be given work exclusively in London, specifically so they might experience aerial bombing.

On the other hand, H R L (“Dick”) Sheppard, returned from volunteering as an Army chaplain in France to resume his post as Vicar of St Martin-in-the-Fields, Trafalgar Square, let it be known that besides prayers for soldiers and sailors he would also lead prayers for conscientious objectors. We know that his ministrations to troops dying on the battlefield began a process leading to his absolute rejection of war and founding of the PPU in 1934. A culminating stage in that process was Dick Sheppard hearing of a sermon on Armistice Sunday, 12 November 1933, by an American Baptist WW1 chaplain, whose denunciation of war, based on similar experience, Sheppard took as the basis of his Peace Pledge.

Another Anglican volunteer chaplain whose experience also led him to pacifism was Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy, popularly known as “Woodbine Willie”, for distributing Woodbine cigarettes as comforts for the troops.

Whilst it is difficult to identify other individual Anglican clergy during the war as being wholly opposed to it, a number of them, including senior members, “would represent to the government that great offence is being given to reason and conscience by the treatment, and especially by the repeated sentences and punishments of some of those who from sincere conviction are bound to refuse military service. We agree with Lord Parmoor [a radical peer] that there is no justification for the terms of successive imprisonment imposed upon them, and with the Archbishop of Canterbury [Randall Davidson] that such treatment should cease.” This memorial was signed in October 1917 by, among others, the Bishops of Lincoln [Edward Hicks], Peterborough [Theodore Woods] and Southwark [Hubert Burge]; Ernest Barnes (then Master of the Temple and later, Bishop of Birmingham - an acknowledged pacifist), Hewlett Johnson (later, Dean of Canterbury) and William Temple (son of former Archbishop of Canterbury Frederick Temple, and himself later Archbishop of York, then Canterbury).

Similar memorials, sometimes shared with representatives of nonconformist churches, were signed by Anglican clergy, one memorial including nineteen diocesan bishops, eight suffragans, seven deans, 200 other clergy and several influential laymen. The Bishop of Oxford, Charles Gore, spoke in the House of Lords about local and appeal tribunals who had misconceived their duties, in particular by attempting to force men, contrary o conscience, into non-combatant service in the military; objectors in such a position were numerous, and he was persuaded that though their bodies might be smashed, their spirit would not be broken; he did not mention it, but one such man in his own diocese had had his training for the priesthood interrupted by his CO experience. Indeed, among hundreds of COs formally designated as ‘CofE’, there were a few other ordinands.

Also, within the Church of England governance, which, apart from Parliament, then comprised the Convocations of Canterbury and York, Lord Hugh Cecil raised conscientious objection in the House of Laity of the Canterbury Convocation, with Lord Parmoor commenting that the one hope of humanity was not to forget the Christian spirit, but to bring it forward on every possible occasion - “Hear, hear”. A resolution for charitable feeling towards conscientious objectors as well as Germans was carried with only three or four dissentients.

|

|

|