|

||||

|

RECLAIMING THE SILENCE |

|||

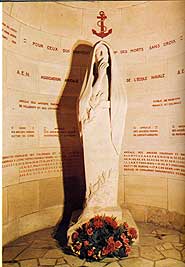

Bathed in red light the figure of silence in Verdun unintentionally symbolises our reluctance to face up to our collective attachment to war.

|

HOW DOES one convey to youngsters growing up today the magnitude of the pain, grief and misery that we have wilfully inflicted on each other during this last and bloodiest century of the millennium? And anyway, is there any point in trying? According to a recent poll, a not insignificant number of teenagers think that ‘The Battle of Britain’ was something Margaret Thatcher was involved in. (Of course, in a sense they are right.) There was much tut-tutting in the newspapers about ‘this appalling ignorance’; the same media continued to perpetuate a misleading picture of a war in which ‘the few’ stood between us and a fate worse than...what? Does it matter? After all, it was so long ago, a new millennium beckons, and shouldn’t we be thinking about the future?... So indeed we should. But the future is the outcome of past and present: there are still a few ‘lessons’ to be learned, before a critical mass is reached and the dominant belief in the efficacy of military solutions is overturned. ‘Battle’ and all those other violent, confrontational words are so overused that they have lost almost all significant meaning. Even ‘genocide’, which one might hope would be reserved for a very specific (and very rare) human crime, is a term now to be found in any sub-editor’s all-purpose stock-in-trade. (‘Ruddy ducks threatened with genocide’ headline in The Guardian) ‘Britain’, however, remains a highly charged word, though its meaning has changed dramatically over the last hundred years. Proud, confident ‘Britain’ stood for naval power and a vast empire at the beginning of the century when its troops crossed the channel to confront the Hun. By the war’s end, two extra-European powers, the USA and Russia, neither of which participated at its start, were pulling strings in Britain and the rest of Europe; and have continued to shape our lives ever since. Similarly, the character of the rest of the century has been shaped and defined by wars – including true genocides (yes, there have been quite a few) – which each November we are encouraged to ‘remember’. Or, rather, ‘those who gave their lives’ in them. ‘Popular interest’ in the First World War has increased in recent years. More time is allocated to it in the curriculum, the number of school trips to the war cemeteries in Belgium and France has grown, and a huge war museum, funded by Britain, has opened recently in Ypres/Ieper. Quite why this is happening is not clear. The ‘heritage’ movement no doubt contributes to it; and perhaps studying and thinking about even this grim past is easier and more comfortable than thinking about – and planning for – the future. Working on the PPU’s interactive CD on war and peace, one finds questions and issues like these cropping up all the time. The utter awfulness of what people have done to each other can probably only be apprehended imaginatively, with the dry statistics of body counts only hinting at the vast scale on which death has been dealt. It is hard to grasp, let alone convey. But because of the many graphic illustrations of violence to which we’re now exposed by way of films, television and computer games, conveying real horror has become difficult too. Even young children, before going contentedly off to bed, can see enactments of atrocities (albeit in representational form) – atrocities which recur lifelong as terrifying nightmares to those who have seen them in the flesh. One begins to wonder if knowing the depravity to which we can sink is all that important. Might it even be counter-productive? How much carnage can one bear before losing all hope for humanity? Without a hopeful vision of the future, life can become meaningless. So: a comforting fudge of the facts can be an appealing option. While the heritage industry and the British Legion differ slightly in their views of war, both essentially see and portray it (even if indirectly) as grim and regrettable yet sometimes necessary and sound in purpose. The pacifist view is a different and subversive one, and all the more difficult for that. Our conviction that war is neither necessary nor purposive challenges those comfortable and convenient formulations of the kind perpetuated every year on Remembrance Day. They were originally devised to give comfort to those bereaved by war, and give justification to the state that embarked on it. ‘They did not die in vain’ implies ‘the war had a valuable purpose’. This is the lie that has been repeated sanctimoniously every day of remembrance since 1918. Just up the road from Verdun, where military incompetence and slaughter almost literally bled the French army dry, is the Douamont Ossuary. Here the bones of 130,000 unknown young men gather dust and an occasional glance from a passing tourist. Above them the marbled hall, which echoes even to the footfall of trainers, is bathed with blood-red light from the stained glass window. Here, in a dark alcove ignored by most, is the statue of Silence which in 1919 stood plainly outside the front door of the provisional ossuary. Slightly bigger than life-size, the figure of a woman with a shawl over her head holds a silencing finger to her lips. The message – that the truth about the futility of the war is best not uttered – is hard to miss. Now, lost in its alcove’s shadows, even this 82-year-old injunction is fading from sight. The awfulness that should not be spoken of has become as irrelevant as the words carved on the skirt of Silence: AUX HEROS INCONNUS. Such words are inscribed in one language or another on war memorials and in war cemeteries round the world. They have proffered heroism as the prevailing, false, and irrelevant explanation of the war – a war in which these dead soldiers have been stripped even of their names. Don’t wait until after eleven o’clock on November the eleventh to break the silence. |

|||