|

| militancy without violence | WOMEN WORKING FOR PEACE |

|

THE MEN WHO SAID NO | ROAD TO CONSCRIPTION | CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTION | PRISONS | SENTENCED TO DEATH | TRIBUNALS | WIDER CONTEXT | INDEX |

||

|

||

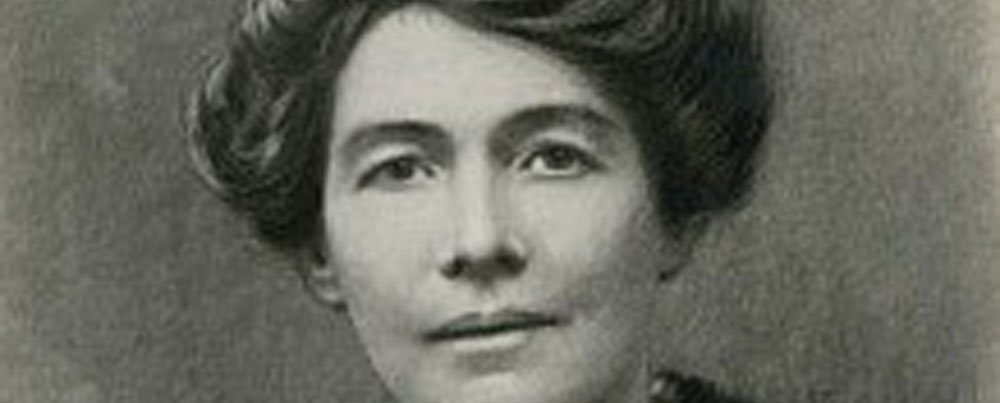

| EMMELINE PETHICK-LAWRENCE | WOMEN WORKING FOR PEACE | |

|

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence was one of only three British women who managed to attend the Women’s International Congress for peace in the Hague in 1915 as she came direct from America where she had been on a speaking tour. Most of the women wanting to attend from Britain were stopped by the Government’s last-minute closure of the North Sea. Born Emmeline Pethick in Bristol, on 21 October 1867, in a large Methodist family, she was sent to boarding school at the age of 8 but was constantly in trouble with her teachers. In 1891 she became a voluntary social worker at the West London Mission, and helped organise a club for young working class girls. Exposed to the poverty around her she became a socialist and a supporter of the Independent Labour Party. She and Mary Neal set up the Esperance club, creating a co-operative dressmaking business with fair wages and working conditions. She also developed a hostel in Littlehampton for holidays for working girls. In 1899 she met and fell in love with Frederick Lawrence, a wealthy lawyer, but refused to marry him till he converted to socialism in 1901. They took the joint surname of Pethick-Lawrence. In 1906 Keir Hardie introduced her to the Pankhursts and she and her husband joined the Women’s Social and Political Union She was soon arrested for trying to speak in the lobby of the House of Commons and spent several terms of imprisonment for suffrage protests. She and her husband started the journal Votes for Women, opened their flat as the office for WSPU and as a place for women to recover from their prison sentences. She became the Treasurer, raising thousands of pounds as well as using a lot of their own funds. Their invaluable organisational support made the WSPU into a national movement. In 1912 the WSPU started a campaign of smashing shop windows, against the advice of the Pethick-Lawrences. While Christabel Pankhurst escaped the consequences by fleeing to France, they were arrested at the office, charged with conspiracy, imprisoned for 9 months, and when they went on hunger strike, both were force-fed. The courts took the contents of their home to pay for the cost of the windows. When the WSPU planned to move on to campaigns of arson, against their advice again, the Pethick-Lawrences were forced by Mrs Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst to leave the WSPU. However Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence stayed friends with Sylvia Pankhurst for the rest of her life, and Sylvia often sought her advice. They carried on with suffrage work, and the Votes for Women paper independently, ‘ militancy without violence’ being their approach. Emmeline also joined the Women’s Freedom League and was its President from 1926-35. When WW1 began, she responded to a request to go to America to promote women’s suffrage, realising she could also encourage them to work for peace negotiations. She spoke at a mass meeting in October 1914 in New York, and travelled around speaking about women and war, writing ‘I believe a great campaign for organising public opinion and its pressure to bear upon the governments of the world could be initiated now by the women’s movement in America…. A world-wide movement for constructive and creative peace such as the world has never seen, might even now come into being - a movement which would influence the immediate development of humanity.’ Her efforts and those of American peace women bore fruit in the Women’s Peace Party, and a huge women’s conference in Washington in January 1915. In April 1915 she sailed with about 50 American women to attend the International Women’s Congress in the Hague, when shipping was at considerable risk of attack by Germany in the Atlantic. The Mayor of New York presented them with a peace flag (PEACE in white letters on a blue background) which the captain hoisted as they left the harbour. At the Congress she moved a resolution demanding that, by international agreement, each country should take over the manufacture and control of arms and munitions - as a step towards complete disarmament, and she supported calls for a conference of neutral nations to offer ‘continuous mediation’ between the belligerent powers. She became active in the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom which grew out of the Hague Congress, and was Treasurer of WIL, the British branch, from 1915-22. To her the war was ‘the final demonstration of the unfitness of men to have the control of the human family in their hands.’ She and her husband opened their country home in Surrey to ‘people who strove to prevent sanity and culture from being swamped by the philistine war.’ In spring 1917 her husband stood in a by-election in Aberdeen on the issue of peace by negotiation, with her support, for which they were both attacked, windows being broken and coal thrown, and hustled off platforms; he only received a few votes. Her husband became a conscientious objector in 1918, and did alternative service as a labourer on a farm. After the war she stood unsuccessfully as Labour candidate for Rusholme, Manchester in 1918, arguing that the only way to prevent a second world war ‘was to make a thoughtful and magnanimous peace’ (the 1919 Versailles treaty wasn’t what she meant). She also advocated independence for India and Ireland. In April 1919 she marched to Downing Street to deliver a resolution calling for an end to the hunger blockade on Germany. She attended the WILPF congress in Zurich in 1919, calling it the most moving experience of her life, as women from former belligerent countries came together. She continued her involvement in politics, supporting her husband’s career - he was appointed a Baron in 1945. She wrote her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World, published in 1938 and died on 11 March 1954.

|

|

|