|

WOMEN WORKING FOR PEACE |

||

THE MEN WHO SAID NO | ROAD TO CONSCRIPTION | CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTION | PRISONS | SENTENCED TO DEATH | TRIBUNALS | WIDER CONTEXT | INDEX |

||

|

||

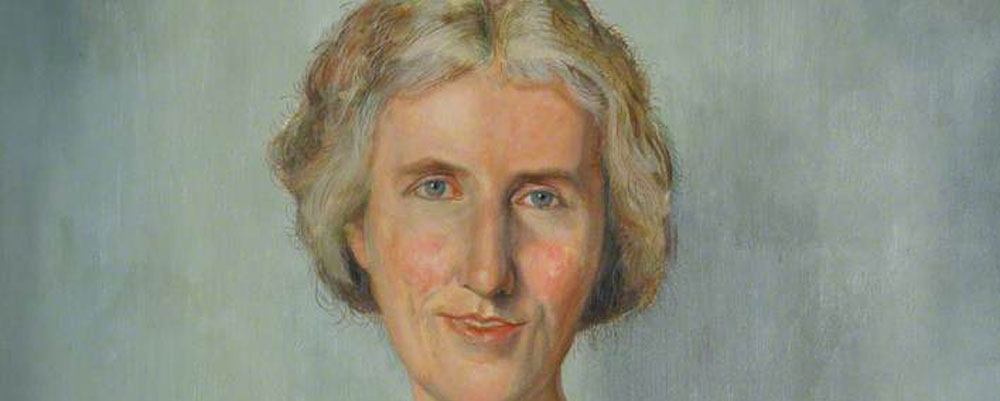

| DOROTHY BUXTON | WOMEN WORKING FOR PEACE | |

|

Dorothy Buxton chose a different form of peace work during WW1, working to make people aware of international views about the war and to show liberal and anti-war opinion in belligerent and neutral countries. After the end of the war, she helped to found the Save the Children Fund to help the children who were suffering so much from the effects of the war. Born Dorothy Frances Jebb on 3 March 1881 in Shropshire and educated at Newnham College, Cambridge, she married Charles Roden Buxton in 1904. He was a Liberal politician at the time, but they both left the Liberal party for the Independent Labour Party during the war, and also joined the Society of Friends (Quakers). When the Women’s International League was formed after the Hague Congress in 1915, she became a member. Dorothy’s peace-time activism took a unique direction. She campaigned against the hatred of foreigners, and worked hard to keep public awareness of international opinion. She ‘could not bear the demonisation of the German people in the British press which she knew would only worsen and prolong the war and make an eventual genuine peace settlement impossible.’ She imported over a hundred papers, including a quarter from enemy countries, via neutral Scandinavia, with the permission of the Board of Trade - it may have suited their purposes to get this information. From October 1915 she collaborated with Charles Kay Ogden, the editor of the weekly Cambridge Magazine, which he had founded as an undergraduate in 1912. His policy was to publish a range of opinions without editorial intervention, so this meant giving room to both pro and anti-war voices, and to all views from the Continent - from allied, neutral and enemy countries. It was Dorothy who obtained, selected and translated the material, with the help of scores of expert linguists, translators and shorthand typists in her Golders Green home. Her life with her two young children had to take a back seat. Her ‘Notes from the Foreign Press’ took up half of the magazine. It did scrupulously present both sides of the debate, giving an account of where the views came from and which part of the political spectrum they were from, such as ’liberal, pro-ally’ or ‘popular, anarchist’ or ‘extreme militarist’. But as a pacifist, she chose to concentrate on ‘questions of pacifist disaffection, international organisation and censorship’. As the material was exclusive to the magazine, it had exceptional influence in political circles. When under attack in 1917 by the pro-war Fight for the Right Movement, a question was asked in Parliament where two Liberal MPs said it was the only place they could read the views of the German press. One of the areas the magazine drew attention to was censorship - the magazine itself rarely got through to subscribers in neutral countries despite complaints to the Foreign Office. Dorothy drew attention to European papers which were censored or eliminated, paying particular attention to Germany where she showed the potential for pacifist protest in a country with no provision for conscientious objection. For example one of her translators wrote about the suppression of the pacifist Berliner Tageblatt, and Ogden praised Maximilian Harden, editor of Zukunft, for daring to criticise German military policy. She published news of socialist anti-war demonstrations in Germany, and views showing that the British hard-line policies only increased support for the German military. After the end of the war, the Allied blockade of Germany continued and a Fight the Famine Committee was created, inspired by Dorothy’s writing from 1917 onwards about the appalling privations of Germany and Austria. The Committee was set up by Dorothy and her sister Eglantyne Jebb, Kate Courtney, Lord Parmoor and Marian Ellis. This was a campaign to put pressure on the British government to end the blockade. A campaigning leaflet ‘A Starving Baby and our Blockade has caused this’ led to Eglantyne Jebb being arrested and fined for distributing it in Trafalgar Square. In April 1919 Dorothy and Eglantyne set up a separate, charitable Save the Children Fund, still a well-known charity today, which was publicly launched in May 1919 at the Albert Hall, aiming to ‘provide relief to children suffering from the effects of war’ and raise money for emergency aid to children suffering from wartime shortages of food and supplies. By January 1920 the International Save the Children Union had been created as similar organisations grew up in other countries. Dorothy’s sister Eglantyne became the honorary secretary of the Save the Children Fund, turning it into a highly effective relief agency. Dorothy concentrated on political campaigning. As Nazi Germany developed, in 1935 Dorothy became concerned about the Nazi treatment of Christians, and she visited to see for herself. She met Hermann Goring to raise concerns about the plight of civilians but he only shouted at her. She collected and circulated reports of the concentration camps she was told about by refugees but the Foreign Office did nothing. Later she came to believe in the need for the war against the Nazis, though her husband still tried to prevent it. During the war she campaigned for the welfare of refugees from the Nazis, and for German prisoners of war. She also once again tried to show the humane side of Germany by keeping in touch with the underground anti-Nazi Christians. She died on 8 April 1963.

|

|

|