|

| WAKEFIELD EXPERIMENT |

CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTION IN |

|

MEN WHO SAID NO | ROAD TO CONSCRIPTION | CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTION | PRISONS | SENTENCED TO DEATH | TRIBUNALS | CONTEXT | INDEX | SITE MAP | |

||

| Back | ||

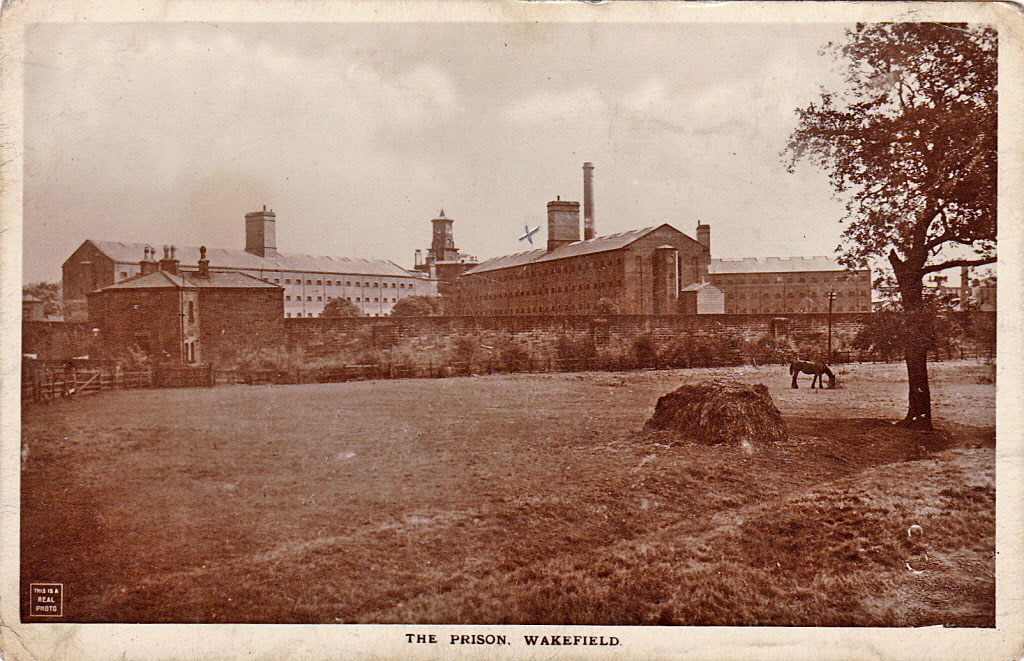

Postcard from a CO. The cross marks location of his cell Postcard from a CO. The cross marks location of his cell |

||

|

|

Back | |

|

The Wakefield Experiment was one of the last, and shortest-lived, attempts made by the government to encourage Absolutist COs to compromise on their principles. August and September 1918 were awash with rumours that a new way of dealing with Absolutist Objectors was on the horizon. Many “two year men” had begun to be released from prison, especially those whose health had been destroyed by prolonged imprisonment. Change seemed to be on the air, and with the war clearly entering it’s terminal stages, COs began to look forward to an imminent release. The Wakefield Experiment was devised as a measure that could prolong the imprisonment of COs, rapidly becoming a political embarrassment for the government as the war wound to a close. It had been planned as a way to involve COs in their own punishment, allowing them to essentially manage their conditions in prison, and therefore keep them locked up without significant protest until the government saw fit to release them. Though a significant compromise on the part of the government, it’s purpose was merely to be a stop-gap measure intended to mollify many of the concerns and protests that had built up over the past two years. It began with men who were long-standing COs who had already served multiple sentences were being gathered into groups in prisons around the country. On Friday August 30th the first of these groups were moved and ten Absolutist COs in Durham Prison, all having served more than two years were told that they were to be transferred to Wakefield Civil Prison. These men were given no choice, and little chance to inform anyone of their whereabouts. Prison officials at Durham had no idea of the conditions at Wakefield, and for many, it would have seemed to be simply another prison transfer. More men would be transferred from Dorchester prison. The Wakefield Experiment The relaxed conditions were earmarked as “temporary” and though COs were freely allowed to report on them from inside, no clear plan seemed to have been made for what the COs would do, how they would be treated, or how the prison would be run. They were initially assigned work to maintain the prison and set up a canteen, an agreeable change from the Hard Labour of other prisons, and the rules that governed their lives were lax. COs had dedicated free time and working hours and could smoke fairly freely. In return for agreeing to not damage prison property and diligently work at assigned tasks From the point of view of the Governor (and government), the conditions of the scheme would have seemed reasonable. If long-serving COs could expect similar treatment around the country, it must have appeared that the problem of the Absolutists was at long last solved. The Wakefield Revolt Work details were light, and with no locks on prison doors and plenty of free time, the imprisoned COs held long discussions over what they would and would not do while at Wakefield. Opinion was divided as to why COs were there in the first place - either to put them under industrial conscription, or to segregate these “Absolute-Absolutists” from the general population, or perhaps even to acknowledge that the prison system had failed. They agreed that they would not submit to prison discipline, would not be put to work they had not agreed to and began to plan a strike. After more than two years of prison, Absolutists were not about to compromise now - even in the seemingly limited way demanded of them at Wakefield. The End of the Experiment After a period of settling in, the Wakefield men had taken it upon themselves to organise and run the prison as they wished. Committees (and sub-committees, those great favourites of peace movements since time immemorial), divided the labour of prison upkeep and cordially invited the wardens to help if they wished. The Governor, with no instructions on what to do, allowed the Chairman of the Committee, Walter Ayles, to represent the official Home Office plan for the prison to the assembled men. Ayles presented the rules and regulations on how COs in Wakefield would be expected to work and live on September 16th. There had been no great threat of exceptional mass punishment, simply that if the rules of the new scheme were not followed, men would be returned to prison. The position was simple. In exchange for their work, COs would stay in Wakefield and be managed, in all essential respects, by themselves. Two days later, with a resounding rejection of the principle of compromising conscience for better conditions, all but six of the 125 Objectors were back in locked cells, soon to be returned to the prisons they came from. The final piece was the creation of the “Manifesto of the Absolutists at Wakefield”. Not only had the COs held there organised and discussed their thoughts, but had formed a Committee which wrote, drafted and distributed a clear statement of intent. The Manifesto signalled the clearest statement of the Absolutist position. Despite better conditions, no manner of compromise would fulfil the aim of the Absolutists: unconditional liberty and discharge from the army. The Manifesto explained that the government: “take for granted that any safe or easy conditions can meet the imperative demands of our conscience. No offer of schemes or concessions can do this. We stand for the inviolable rights of conscience in the affairs of life.” The 123 men at Wakefield refused any form of compromise with the government and demanded either release, or a return to prison. No change in their circumstances could win them over and put them to work. The position outlined in the Manifesto had been the Absolutist stance since before Conscription had become law, and the rejection of the Wakefield Experiment was the last attempt by the government to subvert or undermine it. The Wakefield men returned to prison, and the incarceration of Conscientious Objectors continued as before. |

|

|