|

| NO CONSCRIPTION FELLOWSHIP IN |

||

MEN WHO SAID NO | ROAD TO CONSCRIPTION | CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTION | PRISONS | SENTENCED TO DEATH | TRIBUNALS | CONTEXT | INDEX | SITE MAP | |

||

| Back | ||

|

||

|

NO CONSCRIPTION FELLOWSHIP |

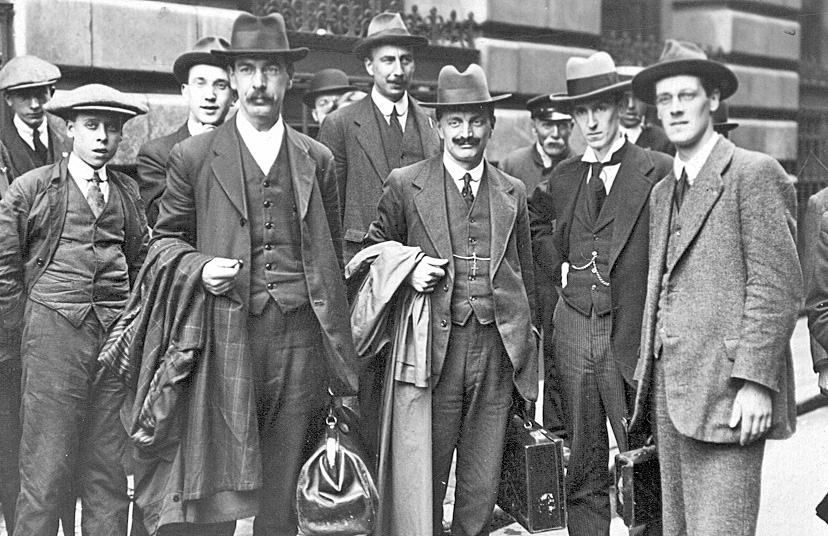

Members of the NCF national committee on their way to prison, July 1916 |

|

|

The No Conscription Fellowship was formed to campaign against the imposition of compulsory conscription. Later, when this failed and conscription became law, the NCF provided support for conscientious objectors throughout the country. The movement began in the autumn of 1914 when, at the suggestion of his wife Lilla, Fenner Brockway - editor of the strongly anti-war Independent Labour Party newspaper Labour Leader - invited those who were not prepared to take part in military service to get in touch. There was an immediate and enthusiastic response. Following a national meeting a new organisation, the No Conscription Fellowship, was formed in November 1914. Its Statement of Faith declared it an organisation of men 'who will refuse from conscientious motives to bear arms, because they consider human life to be sacred and cannot therefore assume the responsibility of inflicting death'. Initially most of the secretarial work was done by Lilla from her home in Derbyshire but with 300 members and growing, new arrangements would soon have to be made; by the beginning of 1915 the membership had become so large it was necessary to open an office in London. Few believed that the government would introduce conscription, which had never happened before in any previous war in Britain, but by July 1915 it was becoming clear that it was being seriously talked about. In August the government took the first step with compulsory registration of men and women up to the age of 65. It introduced the Derby scheme of enlistment, which although nominally voluntary, aimed to persuade all men to take the military oath and enormous pressure was put on them to comply. Despite the millions who had joined up in the first months of the war, the enormous military losses suffered by Britain were rapidly thinning the ranks. It was also clear that the war was going to last a long time. In January 1916 a Bill forcing men into the military was passed and the Military Service Act became law in March 1916. The NCF was organised meticulously, keeping records of every CO, the grounds of his objection, his appearance before tribunals, civil courts, courts martial, and even which prison or Home Office settlement they were in. They also maintained contact with COs, arranging visits to camps, barracks and prisons across the country. Pickets of prisons were held. The NCF also had a press department, which constantly sought to draw the attention of the public to what was happening to COs and the ill-treatment and brutality many were subject to. They also published leaflets and pamphlets and from March 1916 a weekly newspaper called The Tribunal. The Political Department briefed MPs and drafted questions to Ministers. The NCF worked with two other organisations: the Friends' Service Committee and Fellowship of Reconciliation. Ranged against them they had the full might of the government, the police, the army, most churches and the jingoist press which whipped up public opinion against COs or 'conchies' as they were labelled. Immense personal pressures were put on COs not just by the state, but also by communities, neighbours, friends, even families. They also had to withstand the pressure to conform when isolated in barracks, army camps and prisons. Some men were shipped to France in May 1916 as the government and army attempted to break their resolve; some were actually sentenced to death although the sentences were commuted to 10 years hard labour. By the war's end at least 100 men died while under state control. Some suffered mental breakdowns. Some 20,000 men refused to fight altogether. Women played a crucial part in the NCF. Firstly as mothers, sisters, wives, girlfriends and friends of the men who often had to face hostility from family and neighbours. Secondly as workers in the organisation itself, especially as male members were gradually moved to prisons. These included Catherine Marshall, who acted as Parliamentary Secretary; Violet Tillard who worked in the Maintenance department, acted as General Secretary for a period and was sentenced to 61 days imprisonment for refusing to tell the police who the NCF printers were; Ada Salter; Gladys Rinder; Joan Beauchamp who was also jailed twice; Lydia Smith who worked in the Press Department. The government tried very hard to suppress The Tribunal, raiding the first printers, the National Labour Press, and dismantling their printing machinery. The NCF had made preparations and had a secret press which continued to bring out the paper. The police raided the offices repeatedly, followed office staff and also took Joan Beauchamp to court. She was eventually imprisoned for 10 days in January 1920. The final convention of the NCF took place at the end of November 1919 at Devonshire House and was attended by over 400 delegates from branches all over the country.

|

|

|